St. Johns: Town of Friendly

Neighbors Had Unfriendly Start

“Just outside the town a sign reads, ‘Town of Friendly Neighbors,’” wrote Esther F. Davis in 1989, “and indeed the community appears to be a peaceful hamlet. This is ironic, considering the town’s early history which began with misunderstandings, bloodshed and unrelenting harshness of nature.” Two of the founders of St. Johns, embroiled in bitter rivalry, became convicted felons, sent off to prison. But both were soon pardoned of their crimes and finally embraced as Arizona pioneers who made valuable contributions to their community and the state.

A former Goldwater Brothers employee at La Paz in 1862, Solomon Barth (1842-1928) started a store near Prescott and then in 1864 a freight business from Albuquerque to Prescott. His wagons crossed the Little Colorado River at the Rock Crossing about 12 miles upstream of the confluence with the Zuni River. Named for a nearby sandstone promontory, the Rock Crossing was on the Indian trail from Zuni to Mesa Redondo. When Camp Apache was established in 1870, the road from that fort to Fort Wingate crossed the river at the same place. The following year Barth settled a number of his freight drivers and their families near McIntosh Spring, five miles upstream of Rock Crossing and about three miles east of the river. It was a wet period in Arizona and the plan was to cut naturally growing hay in the Little Colorado River valley and ship it to both forts for sale to the government.

Jose Saavedra (1851-1931), from Cubero, New Mexico, the same town that had been home to most of Barth’s drivers, arrived in 1872 and laid out a farm on the west side of the river about five miles upstream of Rock Crossing. Within two years he and his father had built a bridge across the river at Rock Crossing and an irrigation ditch to his fields. At that time, Barth’s drivers moved from MacIntosh Spring, west to the river, where they established a town on the east bank. They knew the location as El Vadito (“little ford”) or El Coloradito, a crossing of the Little Colorado on the road from the Plains of San Augustine and Salt Lake, New Mexico to Camp Apache.

This is a photo of a brand new toll bridge at St. Johns, looking to date from the 1890s. It’s not the bridge at Rock Crossing, more likely at the east end of Apodaca Street. By the time Barth arrived, and obtained a franchise in 1879 from the territorial government to build a toll bridge at El Vado, Saavedra’s 1874 bridge at Rock Crossing was already in use. But there was another road from New Mexico that passed by McIntosh Spring and crossed the Little Colorado at the present site of Commercial Street in St. Johns. The bridge in this picture was probably built to replace an earlier bridge that crossed at Commercial Street. Then this bridge must have been lost in the flood of 1905 or 1915. Concrete piers that once supported a twentieth century bridge can still be seen at Apodaca Street. But today, the river is again crossed at Commercial Street.

In 1875, a few more families arrived, including Maria San Juan Baca (1842-1913). By 1877, Solomon, his wife Refugio (ca1856-1921), and his brothers Morris (1850-1885) and Nathan (1852-1935) had also become residents. The little town on the east bank of the Little Colorado had grown to 100 families. It was decided to name the place San Juan, after Mrs. Baca. That way the community on a river would have John the Baptist as patron and would celebrate St. John’s feast day, the most popular holiday in Sonora, Mexico and among several Christianized Indian tribes. Moreover, the Catholic Bishop in Tucson was John Baptist Salpointe (1825-1898) and the Archbishop of Santa Fe was John Baptist Lamy (1814-1888). However, several accounts of the Hispanic town in 1877 by English speakers Anglicized the name to “Saint Johns, or “St. Johns.”

These two maps surveyed 11 years apart show that St. Johns shifted from the east side to the west side of the Little Colorado River. The map on the left, from 1875, extends about 2.2 miles top to bottom, while the map on the right, from 1886, is about 16 miles high. I have added labels in red. The square mile in the middle of the 1875 map is Section 27, Township 13 North, Range 28 East from the Gila and Salt River Meridian (640 acres). The house on the hill west of San Juan may be Jose Saavedra’s house built in 1875, first on the site of present day St. Johns. And that is probably his ditch and field on the upper section line. Two more fields are shown at lower right. Little Reservoir would be built in the arroyo several years later. Another shallow reservoir nearby was called the “Pathery,” an Anglo corruption of Padreria, meaning “of the Padres.” These two reservoirs are shown on the 1886 map. The Wood Road is today’s Salt Lake, New Mexico Road. The surveyor labeled the land around St. Johns as “bottom land.” The map on the left is a detail from the US Surveyor General map surveyed in March 1875 and now held by the Bureau of Land Management. The map on the right is a detail from the USGS 1:250,000 topographic quad surveyed in 1886 and issued in 1892.

This photo of the San Juan Day parade is dated 1904 and is possibly one of only a handful of views of the Hispanic community of San Juan on the east side of the river. I think the view is looking east with the river behind the photographer. But it’s hard to place the location today. The holiday was popular because it coincided with the summer solstice just before summer rains began, marking an important agricultural season in the southwest. The Monarch Saloon was owned by Walter Darling in the 1880s and J. R. Armijo (1843-1921) by the 1890s. Armijo was a sheep and cattle rancher who served as a Republican county supervisor three times and county recorder once. He later moved to Oak Creek Canyon.

Cruz Rubi (1817-1919) built Rubi Ditch on the east side of the river and a diversion dam called Rubi Dam to feed his ditch. At least two other ditches, the Barth Ditch and Clement Ditch, irrigated meager crops by 1880. Also by then, commercial and residential buildings had been added on the west side of the river. Several Hispanic families accumulated wealth by herding sheep and a few owned businesses. They clashed with Texas cattle outfits, which had moved into northern Arizona after the railroad came in 1881. Over-grazing combined with a fall in wool prices ended the dominance of sheep in Apache County by 1888.

Ammon Tenney (1844-1925) arrived in 1878, to locate sites for Mormon immigrants from Utah and thereby extend the Little Colorado settlements into the White Mountains. A few Mormon families settled near the Rock Crossing, calling their place The Meadows. November 16, 1879, Barth sold Tenney land and water rights on the west side of the river, including a bridge. The price was not cheap, 750 head of average American cattle, but Barth knew Tenney had deep pockets. The LDS church owned 220 head already close by, while William J. Flake (1839-1932) offered to loan another 100 head to make the 320-head down payment. The Mormons believed they had just purchased all the land and water rights on the west side of the river from Rock Crossing to San Juan. They thought Barth and the Hispanics would leave the area. Barth believed that Mormon families would work for him and purchase goods from his store. Both would quickly be disappointed.

Barth sold land occupied by 17 Hispanic families and only “owned” through squatters rights. It had not yet been legally homesteaded. Barth controlled the economy of San Juan, though other non-Hispanic businessmen were arriving every day. In those days, income came in only a few times a year so families likely ran up a tab at Barth’s store. That way he may have had an informal lien on their property, and thus be able to sell it out from under them. In any case, Saavedra lost his home and farm and moved south about 12 miles to El Tule. Several other Hispanic families left the area after losing their land in the sale. Mormon families began building log cabins and leveling fields a little over a mile northwest of San Juan, naming their community Salem. They established a Salem Justice Precinct and applied for a post office. At first the “Mexican” families were friendly, but they soon realized how much they had to lose.

Salem was located in swampy bottomland, an area the Mormons called Egypt. In October 1880, Salt Lake City church leader Erastus Snow (1818-1888) recommended moving Salem to higher ground bordering San Juan on the west and north. A church leader from Snowflake, Jesse N. Smith (1834-1906), and newly arrived settler David King Udall (1851-1938) located a public square two blocks west of Barth’s home and began surveying lots, alarming the Hispanics. It was obvious that the Mormons aimed to take control, even creating a new town center and realigning roads on the west side of the river where Barth and some Hispanics already lived. November 18, Mormon leaders obtained a Quit Claim Deed in an attempt to further clarify what they had purchased. Now it was 1,200 acres and about 60% of the water rights in exchange for 770 cows and $2,000 in other property. Udall helped herd the final payment of cattle all the way from Pipe Spring in February 1881. But land ownership would remain a problem, until in 1888 St. Johns organized under federal and territorial townsite statutes.

A. F. Banta (1843-1924), who had once driven freight wagons for Sol Barth, combined his influence with Barth’s at the capitol in Prescott to split the vast Yavapai County in two in 1879, creating Apache County out of the eastern part. This cut stone courthouse was built in 1884. A jail with a metal roof was added on the east side in 1885. In 1891, Apache County was split in two to create Navajo County from the western half. In 1917, county officials had the existing courthouse built on the hill where the white schoolhouse was located and the old courthouse building became an elementary school.

For the next thirty years a battle for economic and political control of the community and Apache County would rage. Four factions developed, the Mormons, the Barth family, the Hispanic community and a group of anti-Mormon Anglos who would be called the St. Johns Ring and who introduced considerable wealth and power into the community. And there would always be dissent within each faction, with crossing of political and family lines. To this political hostility the 1880s added economic hardship from drought. Barth tried to keep tight control of county government and ran successfully for the territorial legislature in 1880 while Bishop Udall called for more colonists to increase his base. However, as historian Charles S. Peterson notes (pp.34-35), “a rapid growth of population notwithstanding, the plan to make St. Johns a tight Mormon community failed. Moreover, the seeds of discord sown in this bid for monopoly cankered the course of the little town’s history throughout the remainder of the century.” At first, Barth may have led the St. Johns Ring, but before long the political machine would turn on both he and Udall.

But first, social and economic tension fueled by drunkenness led to bloodshed. June 24, 1882, the Greer boys, a semi-Mormon gang of under-employed cowboys originally from Texas, showed up in St. Johns on San Juan’s Day. A gunfight broke out between the Greers hold up in a house on Commercial Street and Hispanics shooting from the upper windows of the Barth home. A couple men on both sides were wounded and one of the Greer gang killed. Then Ammon’s father, Nathan Tenney (1817-1882) walked down the street and into the house where he convinced the Greers to come out with Apache County Sheriff E. S. Stover (1839-1920s). But as the group emerged, a bullet from the Barth home instantly killed Tenney. Violence flared again when Sol Barth and A. F. Banta went at each other’s throats in a drunken brawl in 1884. Sol’s brother shot Banta in the throat, blasting away the tip of Sol’s thumb in the process and others had to grab Banta to keep him from returning fire. Banta survived. The argument passed and he and Sol continued as political allies.

The Edmunds-Tucker Act, passed in 1882, made polygamy a federal offense. This gave the St. Johns Ring a way to rid the town of Mormons by using criminal prosecution against polygamy, practiced by only a small minority in the church. Polygamy trials would also gain votes for Republicans who would take political control away from the Barths and the Mormons, both staunch Democrats. Single-issue campaigning worked to throw elections in those days just as it does now. The plan seemed to succeed at first, then, quickly backfired.

Stover was elected to the territorial legislature in 1884 where he pushed through a law that would bar Mormons from voting based on their immoral conduct. Previously, the Ring simply stuffed county ballot boxes. The same year, a St. Johns resident was indicted for polygamy, then, both of his defense witnesses charged with perjury. One of the witnesses, D. K. Udall was convicted of perjury and sent to federal prison at Detroit in 1885 along with three other St. Johns polygamists. Two more plea-bargained for shorter sentences at the Yuma territorial prison. A sixth skipped bail. Meanwhile, Democratic US President Grover Cleveland had been elected in November 1884, ending a succession of six Republican administrations. Cleveland pardoned Udall before the end of 1885 and the main street in St. Johns became Cleveland Street. And the Bishop’s next son was named Grover Cleveland Udall (1887-1950).

The winds of change blew a gale through the dusty town. Two St. Johns newspapers had been rabidly anti Mormon while Mormons printed a third. But in April 1886 the new editor of the St. Johns Herald pledged fairness and good journalism. The Apache County elections of 1886 and 1888 pitted the Republican “Citizens Ticket,” led by a group of cattlemen, Sheriff Commodore Perry Owens (1852-1919), Robert E. Morrison (1856-1927) and E. S. Stover, against “Equal Rights” Democrats led by the Barth’s, most Hispanic families, and former Sheriff Lorenzo Hubbell (1853-1930). The Democrats won every office but one. Over the next ten years, most of the St. Johns Ring left town. St. Johns has been controlled by conservative Democrats ever since.

Beginning in June 1884, Sol Barth was arrested several times for business fraud, forgery and tampering with county records. He was finally convicted of forgery in 1887 and sentenced to 10 years in Yuma prison. The Arizona Supreme Court upheld the conviction and Barth reported to prison as probably its wealthiest resident. Refugio Barth went to Prescott to see the Democratic Governor appointed by President Cleveland who eventually issued a pardon in 1889. Then Barth was elected to the upper house of the legislature in 1897.

This view of St. Johns in 1890 is from the southeast slope of what would become Airport Hill looking southeast toward the Great White Schoolhouse on the Hill. The two-story building at left-center is the brick tithing office (1885), where secondary school classes were being held on the second floor. By 1890, population had declined to 482 from 546 ten years before. Drought and excessive alkalinity in the soil had driven many families away. Others left to escape the politics. Photographer Welcome Chapman (1849-1900) was a stonemason who worked on Salado Dam and was known for his engraved tombstones. He also had a camera with which he took many commercially sold photos.

Not legible in this view of dusty Commercial Street about 1900 is a white sign on the right marking the Post Office. The record of how St. Johns got its Post Office has been purposefully confused. Mormon colonizer Sextus E. Johnson (1829-1916) was appointed Postmaster of Salem April 5, 1880 but was “refused his keys” by anti-Mormon political boss E. S. Stover. Stover got the Salem Post Office discontinued June 8 and then reestablished July 26 as “Saint Johns” with himself as Postmaster. In the process, San Juan became Saint Johns, an equivalent used on the earliest maps, and all record of Salem was expunged. There is also an account of refusal by bureaucrats in Washington DC to approve a post office application in 1877 for “San Juan” because all the names on the application were “Mexican.” The picture shows the principle business district, still in the hands of non-Mormons. The leaning telephone pole marks the river, with some of the buildings of old San Juan beyond. Telephones came to St. Johns in 1898 and then again in 1907. The men at right are standing in the road from Springerville, opposite Barth’s home (at left). By 1900, there was a single block of Mormon businesses behind the photographer. Today, all these buildings are gone, but this point on Commercial Street still marks the division between the Anglo and Hispanic neighborhoods.

Even during the relatively wet years of the 1870s, St. Johns crops required irrigation. But the Little Colorado River was given to erratic flows, almost drying up then raging with floodwaters. At least six dams at St. Johns washed out, each time bringing the community to its knees. A small storage reservoir built in the early 1880s adjacent to the town on the north held about 60 surface acres. Little Reservoir (1885), of about 125 surface acres about a mile south of town, was fed by a canal from brush diversions like Rubi Dam. In the summer of 1916, Henry C. Overson (1868-1947) built the first concrete weir on the river to send water into Little Reservoir. The first Salado Dam (a.k.a. Slough) six miles south of St. Johns formed a lake with 2-3 miles of shoreline. It washed out in 1886, ironically a year of severe drought, and was rebuilt by 1887. The harvest of 1887 was thereby the first adequate harvest. The record is incomplete, but there is also a report of a dam at Salado nearing completion in 1894. In 1897 Salado Dam was reported to be 900 feet long, creating a 600-acre lake.

Still, water was inadequate and saline. Drinking water had to be transported from McIntosh Spring and sold by the bucket. After five years, most of the Mormons were starving. They had insisted on raising cattle instead of animals more suited to the high desert, like sheep. And instead of drought-resistant corn, they preferred irrigated wheat. But mineral springs at Salado were ruining crops at St. Johns. After struggling for twenty years, in February 1900 Mormon families in St. Johns were told by church authorities in Salt Lake City that they were released from their “call” and free to leave. Others had already been released years earlier to escape criminal prosecution and starvation.

By 1903 a larger reservoir 40 feet deep and five or six miles around at Salado had been created by constructing a rock and dirt dam only 150 feet long and 150 feet thick. But the long dry spell ended and more than a decade of deep snows in the mountains and heavy winter and spring runoff began. New Salado Dam was overtopped and destroyed May 2, 1905. The population of St. Johns had already peaked in 1885, continuing to decline until 1910. That year, a land development company in Denver started work on Lyman Dam upstream from Salado, with a long canal bringing better quality water to St. Johns. The LDS church contributed $5,000 toward the work. But a few years after it was finished the earthen dam broke April 14, 1915 drowning six children and two adults, and taking out every bridge and dam downstream to Joseph City. It was a devastating loss of life, property and invested money. When local residents failed to raise enough money, Lyman dam was finally rebuilt 1919-1921 by the Arizona State Loan Board. But the cost was more than three times the amount required to build the first Lyman Dam. Water users had difficulty repaying the loan, but after the state legislature cancelled half the debt the remainder was repaid by 1941.

When the new courthouse was dedicated April 2, 1918, the old building became District 1 elementary school shown here. The building on the right was the town’s second jail, built in 1885. The school burned in the early 1930s and was rebuilt as Coronado School. It was demolished after a new building was constructed in 1987 on the playground. It had remained a segregated school for Hispanic children until the 1954 US Supreme Court decision forced integration. One source gives 1956 as the year of a petition to finally integrate St. Johns schools. Henry and Margaret Overson had a photography studio in St. Johns. Margaret (1878-1968) was usually the photographer while Henry ran the Little Reservoir irrigation system. She continued taking photos for more than 50 years.

LDS parents didn’t like their children attending the public White Schoolhouse on the Hill along with Hispanic students. As a result, some LDS kids attended class in the log cabin Assembly Hall (1881) until a brick elementary school could be finished in 1912. School District No. 1 was divided in 1910 to create District 11 for Mormon kids. With integration, the school districts consolidated in 1957. Mormons established the first secondary school, St. Johns Stake Academy 14 January 1889, using rooms in the brick tithing office building. Work began on this two-story brick Academy building with the cornerstone 1 May 1892 but it would take years to complete. Classes had to be suspended due to lack of funding in the spring of 1892, not to resume until the new building was almost finished. It was dedicated 16 December 1900. In 1921, church authorities in Salt Lake City ordered all the private academies closed and LDS students to attend public schools. After the public high school building was built next door, the Academy building was used for church services. It’s still there, incorporated into the structure of the downtown chapel.

Sometime between 1874 and 1879, Sol Barth had this large home constructed on the main east-west wagon road where the road from Round Valley dead-ended on the west side of the river. After his children grew up Barth turned the house into the Scott Hotel and then the Barth Hotel. This photo from 1914 commemorates a trip by Gustav Becker of Springerville to promote the National Old Trails Road. It was a main cross-country highway from Holbrook to Concho, St. Johns, Springerville and into New Mexico until the 1930s. Gustav is at the wheel of the first car on the left, while brother Julius is driving the next auto. Standing in the middle are Clara, Refugio, and Jake Barth with Sol in the dark hat. Barth Hotel closed in the 1930s and was demolished in 1984.

According to records of the Diocese of Gallup, the “Saint Johns (San Juan) – Saint Johns the Baptist Parish” was established in 1877. The Rev. Pedro Maria Badilla (1827-1901) arrived in St. Johns to lead the parish 2 August 1880 and found a church was already under construction. The building, shown here about 1920, was dedicated as San Juan Bautista church in 1881. It was replaced with a new building just to the left constructed in 1941 and dedicated 21 June 1942. Franciscan sisters came in July 1957.

Barth Hotel Cottages was built in the 1920s on the southeast corner of Commercial Street and the highway to Springerville, across the street from the Barth Hotel. Within a few years of adopting a numbered federal highway system in 1926, traffic on the National Old Trails Road subsided. St. Johns became an isolated rural hamlet as motorists took Route 66 into New Mexico. Population stagnated at around 1,300 from 1920 until 1975.

Judge Levi S. Udall (D.K.’s son) described his hometown to a gathering at the Arizona Museum in Phoenix in April 1946 as having progressed beyond its earlier history of lawlessness. He said the Superior Court had not had “a jury term of court since February, 1943 (more than three years ago). Furthermore, our jail is empty more than half of the time and juvenile delinquency is at low ebb. I feel that these facts speak well for the attitude of the Apache County citizenry on law observance.” Actually, it said more about policing, since many infractions were handled informally in those days and a number of young men were off at war. A few years before, Levi’s sons stole a car for a joy ride but were punished without jail time or a criminal conviction. In addition, the poor economy and loss of travelers to Route 66 kept the population from growing and crime low. Southern Apache County has always had more cows than people.

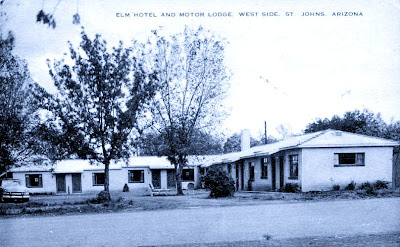

D. K. Udall had a large home he called The Elms built in 1912 across Cleveland Street from the Stake Academy and later High School building. After the elder Udall’s death, son Grover and wife Dora (1886-1976) moved into the house. When Grover died in 1950, Dora opened The Elms Dining Room in the home and had construction begin on ten motel units in the back yard. The Elm motel opened in 1952. The Udall family produced a number of noted educators, lawyers and politicians. One of DK’s sons became mayor of Phoenix, another served in the state legislature, while two more sat on the state supreme court. Grandson Stewart Udall (1920-2010) was a member of Congress 1955-1961 and Secretary of the Interior 1961-1969, and grandson Morris “Mo” Udall (1922-1998) served in Congress 1961-1991 and ran for president in 1976. In fact, over the years, St. Johns probably produced more public figures than any other town of comparable size in the state.

In 1937, a large chapel with a steeple (at right) was added to the east side of the old Academy building (at left). This postcard view shows the combination Stake Center and Ward Chapel in the 1940s. St. Johns High School is just out of view at left. A new Stake Center was built across town and dedicated July 24, 1983, but this building is still the downtown chapel.

When the LDS opted for public schools instead of private academies this cut stone High School was completed in 1926. It was replaced by a new campus on the west side of town in 1981 and is now used for county offices.

With poor soil, harsh weather and isolation, making a living in St. Johns was always hard. Throughout its history, a large number of residents of the county seat required welfare benefits. In 1880, residents of Sunset (near Winslow) donated barley for families at The Meadows, described by D. K. Udall as “destitute saints.” Drought led to abandonment of The Meadows soon after. In September 1885 the LDS Church in Utah sent two railroad boxcars of food to keep the brethren in St. Johns fed. Then the church gave $2,500 in cash to buy wheeled scrapers for building Salado Dam. In the twentieth century federal government welfare carried families through economic recessions. Here, government commodities are unloaded for distribution behind St. Johns High School. Farm Security Administration photographer Russell Lee made the color slide, now in the Library of Congress, in October 1940. He found families in nearby Concho doing a little better.

Commercial Street, a three block long business district ended up in the middle of blocks surveyed by Mormons in 1880 because Barth’s home and a few other buildings had already been built on what was then the main wagon road from Socorro to Ft. Apache. But that fortuitously placed businesses on higher ground and gave convenient access to rear loading docks without the need for alleys. The early business district was compact, providing everything within walking distance. This view from about 1949 is looking west from the same point shown in the ca1900 photo above. The Barth home is at right, with Barth Mercantile, the Maytag dealer, just beyond. Across the street, where the telephone lines run, is Cowley Brothers Supply on the former site of A & B Schuster store (1891-1915). A hospital opened in St. Johns in 1949 but closed in 1962 when paying the bills became too difficult. Though the town was set apart in 1888 to establish land ownership, town government was not incorporated until 1946.

Commercial Street, seen here about 1953, was the largest commercial district in the entire White Mountain area. E. T. “Ernie” and Josephine Wilbur opened Wilbur Food Market shortly after coming to St. Johns in 1932. The location shown here was occupied beginning in 1936. The stone Whiting Block and all the other buildings on the block were rebuilt after a 1942 fire. The Whitings also operated the Ford dealership, while the first service station in town (1922) was across the street at Patterson Motors Chevy dealership. Whiting Brothers, Arthur, Eddie, Ernest and Ralph, managed a family empire that grew to at least 14 sawmills, four auto dealerships, 44 service stations and more than a dozen motels across the southwest.

This view of Commercial Street about 1967 looks east from a point about 100 feet east of the photo directly above. Whiting Ford is at left with Patterson Chevrolet at right. The Arcadia Theater and a couple other buildings have been combined to house Triple S Market. When power plant workers came in the 1970s, many businesses left Commercial Street for new locations on west Cleveland Street. Today, the business district is a two-mile-long strip development designed for reliance on automobiles. Norm Mead (1923-2008) of Mesa published the postcard.

In late 1974, Salt River Project selected a site for an electric generating station less than 10 miles north of St. Johns. The following year, construction brought an influx of 2,800 Bechtel workers into the community of 1,500 people. The economy of St. Johns was transformed. Though government employment in the southern county remained at around 60% of the workforce, high-paid power plant jobs boosted average family income, eclipsing those who remained in poverty. Once construction workers left, the population of St. Johns settled at a few hundred more than 3,000. But now there were once again three demographic groups. The Hispanic and Mormon pioneers had been joined by a third group of non-Hispanic, non-Mormon residents.

A few years ago St. Johns again quaked with political scandal and violence. Two judges were removed from the bench for ethics violations that would not have been noted even in the back pages of the newspaper in the 1880s. Then, the Apache County Sheriff was accused of theft and removed from office. Finally, St. Johns headlines flashed around the world after a father and his friend were ambushed and shot to death in their own home by the eight-year-old son. That shock was followed by arrest of a teenage serial killer.

See:

William S. Abruzzi, Dam that river!, (1993)

Apache County Centennial Committee, Lest Ye Forget, (1980)

Esther F. Davis, “St. Johns,” (1989) unpublished manuscript.

Joseph Fish, “History of Eastern Arizona Stake of Zion: Early Settlement of Apache County,” [1912] unpublished manuscript held by ASU Library.

N. H. Greenwood, “Sol Barth: A Jewish settler on the Arizona frontier,” Journal of Arizona History, Winter 1973, pp.363-378

Charles S. Peterson, Take Up Your Mission, (1973)

Wilford J. Shumway, St. Johns Arizona Stake Centennial, (1987)

St. Johns Arizona Stake, Solomon Barth 1842-1928, [2004]

Cameron Udall, St. Johns, (2008)

David King Udall, Arizona Pioneer Mormon, (1959)

C. LeRoy & Mabel R. Wilhelm, A History of the St. Johns Arizona Stake, (1982)

Charles B. Wolf, Sol Barth of St. Johns, (2002)

Sonoran Desert field trip guides

6 years ago