Part Three:

Arizona’s Indians Regained Lost Homelands

Federal policy toward American Indians changed over the years as political leadership in Washington DC changed. At first a policy of Indian removal forcibly relocated native residents farther west to provide free land for white settlers. When genocide proved impractical, tribes were confined to reservations with as little acreage as possible even if that meant providing welfare commodities for Indian families. Finally, in order to take back even these reserves, the government adopted a policy of assimilation and termination. Indians would be converted into economically self-reliant Christians who complied with societal norms, and reservation segregation would be abolished.

An Act of Congress March 3, 1871 ended treaty making with tribal chiefs. Indians would no longer be treated as foreigners. Since citizenship in this country had been traditionally tied to ownership of real property, Congress passed the General Allotment Act February 8, 1887 (Dawes Act) to parcel out reservation land to individual families, converting it to deeded, taxable acreage. By 1920, Indians across the country had lost two-thirds of their land at tax sales or to repay debt. Some of what remained had been divided among heirs until it had been reduced to useless fragments. To end allotment, Congress went back to creating reservations (1907), bestowed citizenship on all Indians (1924) and provided for tribal governments (1934).

Then the termination policy came with the Eisenhower administration, giving states the option to extend criminal justice jurisdictions over reservations (1953), giving tribes the option to permit the sale of alcohol on reservations (1953) and transferring Indian health care from the BIA to the US Public Health Service (1955). Arizona chose not to take on the cost of policing reservations. Some tribes outside Arizona were talked into giving away their reservations. Then, beginning in the 1970s, a number of reservations lost through allotment were restored, new tribes were recognized, reservation boundaries expanded, and water rights restored. The Indian Gaming industry was created to provide revenue that would in theory replace welfare. And freshly trained Indian lawyers turned to the pre-Eisenhower Indian Claims Commission Act of 1946 for restoration of aboriginal lands or compensation.

The Pai tribes

The Pai (“we people”) in Arizona includes three tribes, Havasupai, Hualapai and Yavapai, sharing a similar culture and speaking mutually intelligible dialects of the Yuman family of languages. Yavapai history was presented in Part Two of this series. Because the Yavapai were associated with the Tonto Apaches, the tribe ended up fragmented across three reservations, developing three different identities based on home territory. As a result, five Arizona Pai tribes are often distinguished, Havasupai, Hualapai, Ft. McDowell Yavapai, Prescott Yavapai and Yavapai-Apache. There is also a sixth Pai tribe, cut off from the others long ago by warfare with the Yuma-Mohave alliance and isolated by the international border between the US and Mexico. Those people are the Paipai.

Building across northern Arizona, Atlantic & Pacific railroad tracks reached Peach Springs in January 1883, the same month a reservation encompassing Peach Springs was created. Thirty years later, the transcontinental National Old Trails Highway, following the rail line, was routed through Peach Springs. In addition, a road from Peach Springs to Diamond Creek offered auto access to the Colorado River in the bottom of the Grand Canyon. There is little indication, however, that the railroad, the highway, or its successor, Route 66, benefited the Hualapai people to any great extent. The motels, cafés and filling stations at Peach Springs were owned by non-Indians. But the town became tribal headquarters, while the BIA agency was located on an island of reservation surrounding the school at Valentine. About half the now 2,100 enrolled members of the Hualapai Nation live at Peach Springs. This view shows a number of families or maybe a single extended family, gathering perhaps to honor the dead, but unlike today’s notion of an entertainment pow-wow. Note the gender and age divisions. The Albertype postcard from about 1916 was published by “A. E. Taylor, Indian Trader” at Peach Springs. For a view of the trading post in the 1920s see my “swastika” post of 9/30/2010.

The Hualapai Nation (Hwal’bay, Xawálapáiy’, Hawálapai, Walapai, Cohonino, Cerbat, Whala Pa’a)

Hualapai Indian Reservation

The military created a reservation for the Hualapai July 8, 1881 and then lobbied to have it made permanent. January 4, 1883, President Chester A. Arthur ordered the creation of the Hualapai Reserve, 1,142 square miles on the south bank of the Colorado River where it runs through the western portion of the Grand Canyon. President McKinley, December 22, 1898, ordered the creation of a Hualapai Indian School Reserve at Valentine, adding another quarter section of land to this reserve May 14, 1900. This enclave became the site of Truxton Canyon Training School (1901-1937), a government boarding school that expanded to enroll students from many tribes.

The Hualapai were only one band among a dozen Northeastern Pai bands, each composed of a number of extended families. Each band lived off the land within a defined territory and identified itself closely with that space. But English speakers saw only one tribe, to be identified by the name of only one band, “Hualapai,” or “The People of the Tall Pines.” They were skillful traders, ranging over a vast area of northwestern Arizona to gather materials to produce specialized products for tribes as far away as the California coast and the Rio Grande Valley.

Hualapai people were friendly to Europeans at first. But when miners came to their land, seizing water sources and killing Indians who got in their way, the Hualapai struck back. Following the Civil War, the US military launched a war on the Mohave and Hualapai. After battling from 1866 to 1869, most of the warriors surrendered and were rounded up at Camp Beale Springs north of Kingman. A few Hualapai fled to Havasu Canyon where they were accepted as guests by the Havasupai. Some estimates count a third of the Hualapai Nation killed during the three years of warfare. By 1874, the military felt it had most of the tribe in custody and relocated families to the Colorado River Indian Reservation, a land and climate foreign to them. The following year, Hualapai began walking away, returning to their homelands in what is now remembered as their Long Walk. Unfortunately, much of their homeland had been taken by Anglos. The US military decided a reservation east of the mining towns might keep the peace.

The Hualapai Nation adopted a constitution and bylaws in 1938, a corporate charter in 1943 and a new constitution in 1970. With more than 80% unemployment, the tribe established Hualapai River Runners in 1973, replacing contracts with non-Indian owned companies. Tribal government embarked in 1988 upon an ambitious tourism venture with the Grand Canyon West development, 70 miles north of Kingman, as the centerpiece. Grand Canyon Skywalk, a glass “bridge” 4,000 feet above a side canyon of the Grand Canyon, was completed in March 2007. Like many other American Indians, the Hualapai have debated whether sacred ground should be opened for economic development, if tourism is better than mining and if Indian enterprises might just be attempts to copy European culture.

Looking down on the village of Supai around 1970, we see the homes of the Havasupai below the twin spires of Wigleeva Rocks (at left), which remind the people of their twin mythical heroes. The view is looking north toward the Grand Canyon with Havasu Creek in the trees, bending downstream to the left. Schoolhouse Canyon is entering Havasu Canyon at upper center. The photo was made in the early 1970s by K. C. DenDooven of K C Publications. Founded in Flagstaff in 1963, K C Publications is now located in Wickenburg.

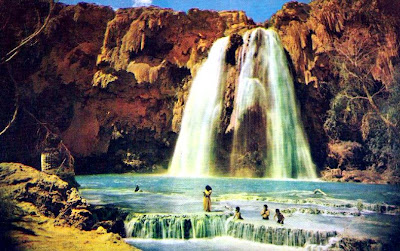

Below Supai, breathtaking waterfalls fill limpid pools surrounded by lush greenery giving the impression of a virtual Eden. This is a picture postcard from before 1954 of Havasu Falls. The photo is by Ray Manley of Western Ways in Tucson, published by Bob Petley of Phoenix. Going downstream from Supai, Havasu Creek tumbled over five travertine terraces, Fiftyfoot Falls (aka Supai Falls), Navajo Falls, Havasu Falls, Mooney Falls and Beaver Falls. Flooding in 2008 altered the course of the streambed, creating two new waterfalls and leaving Navajo Falls dry. Before the reservation was expanded in 1975, the National Park Service maintained the trail into the canyon and controlled the campgrounds at the waterfalls.

The Havasupai Tribe (Havsuw ‘Baaja, Ahabasugapa, Havasooa Pa’a, Yavasupai, Suppai)

Havasupai Reservation

June 8, 1880, President Rutherford B. Hayes ordered the creation of a 38,000-acre “Suppai” reservation in Cataract Canyon, along Cataract Creek (now Havasu Creek), a tributary of the Colorado River in the western part of the Grand Canyon. Hayes replaced his order with a slightly corrected version November 23, 1880. After an army survey found Anglo-owned mines within reservation boundaries, President Chester A. Arthur reduced “Yavai Suppai Indian” land March 31, 1882 to only 518 acres in the canyon. Indigenous families lost control over hunting and gathering lands essential for their support. And when Grand Canyon Forest Reserve was created in 1893 and Grand Canyon National Monument was created in 1908, the Havasupai found their aboriginal lands above Havasu Canyon restricted and patrolled by Forest Rangers and Park Rangers. Population declined from about 300 Havasupai in the 18th century to a low of 166 in 1906. A tribal government was organized in 1939. In 1975, reservation boundaries were enlarged beyond the canyon to include 185,516 acres. Of the now 650 enrolled tribal members, about 450 live at Supai.

Rather than a separate Pai nation, many consider the Havasupai one of the Hualapai bands. The “people of the blue-green waters” enjoyed less contact with English speakers over the years than any other Arizona tribe. Still, Indian agents and missionaries rode into the canyon to live and worked to assimilate the natives. A stone schoolhouse was built in 1895 but destroyed in a massive 1910 flood. It was replaced, and a Christian church was also built. For many Havasupai, the sweat lodge experience still provides the most intimate connection to the spirit world. The Paiute ghost dance religious movement spread to Arizona by 1889 and proved attractive to the Havasupai. While the Hualapai became disillusioned with the movement in 1891, the Havasupai are reported to have continued the practice until 1901.

In Havasu Canyon there was plenty of water, protection from wind and a warmer climate at the reduced elevation. In their bucolic isolation, the Havasupai tended fields, venturing out of the canyon to find what they couldn’t grow. By the 1960s, Supai had a post office, general store and medical clinic. But everything still came by horse pack train down the trail or by helicopter. In 1971 the old diesel electric generator in the canyon was replaced by a transmission line and two larger generators up on the plateau. But there has been trouble even in paradise. A Japanese tourist was recently murdered on the trail to Supai. Then devastating floods in August 2008 and October 2010 closed the canyon to all visitors, cutting off the major source of income.

The Paipai (Akwa'ala, Pai Pai, Kumeyaay-Paipai)

The Paipai are one of more than a dozen tribes of the Kumeyaay-Diegueno Nation of southern California and Baja California Norte, Mexico. A small number of Paipai live in the community of Santa Catarina, Baja California Norte. They began visiting Arizona’s Verde Valley in 1999 to share traditional knowledge with their Yavapai cousins.

Students line up neatly at Fort Yuma Indian School around 1900. The institution has now been reorganized as San Pasqual Valley Unified School District, named after a noted Quechan chief. The small boys in front are clothed in the finest fashion available for young American boys of that era. The older boys in back are wearing military cadet style school uniforms. All of the girls are dressed conservatively, in rather long dresses for the time. Europeans were scandalized when they first encountered Yuma, Pima and Maricopa women who traditionally went around bare-chested. Ordinances were adopted requiring women to cover up when going to town. Fort Yuma, established in 1850, was abandoned by 1883, whereupon the school took over the former military buildings. Situated on a high bluff across the Colorado River from the town of Yuma, paradoxically, there was not enough water to grow shade trees and the school high on wind-swept Indian Hill was a rather dismal looking place until more water became available.

At the same location as above, only sixty years later, the Quechan Indian marching band poses in front of their San Pasqual school bus. Though the signs say Yuma, Arizona, the Fort Yuma site and San Pasqual School are on the California side of the river. Shade trees, palms and one of the old military buildings are visible in the background. The feathered war bonnet of the plains tribes became such an icon that Indians in Arizona who traditionally did not wear such headgear often put it on to look the part. Most didn’t mind. Despite strong tribal identities, pan-Indian traditions continue to strengthen solidarity across boundaries. Last year, the annual Quechan Indian Days celebration honored this marching band which used to travel all over the country. Now disbanded, it was created longer ago than anyone can remember. There are postcards dating back to the 1930s and a reference to a performance in 1914.

The Quechan (Yuma Indians)

Ft. Yuma-Quechan Tribe

In 1853, the Department of Interior established via administrative order a reservation for the Yuma tribe in the area surrounding Fort Yuma. President Chester A. Arthur issued an Executive Order July 6, 1883 creating an unnamed Indian reservation for the Yuma tribe in Arizona Territory. When word came back to Washington, that the Quechan didn’t live in Yuma, Arthur cancelled the reservation in Arizona January 9, 1884 and established a reservation in California, giving the abandoned military reserve to the Department of Interior, US Office of Indian Affairs, forerunner of the BIA. The tribe lost much of its reservation 1893-1910 through allotment. By 1910 tribal population had reached a low of 750 individuals remaining from the population estimate of up to 4,000 made by the Spanish when they first encountered the Quechan in the 16th century. In 1978, the federal government returned 25,000 acres to the Fort Yuma Reservation and by 2000 the population had reached 2,376. It is now the second largest reservation in California.

Spanish explorers Alarcón (1540), Onate (1603) and Kino (1698) first encountered the Yuman speaking tribes on the lower Colorado River. Father Garces helped establish two missions near Yuma crossing in 1780, San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer and Misión Puerto de Purisima Concepción. Both were located on the west side of the river. After soldiers and colonists joined the missionaries, the Quechan rebelled against Spanish control in 1781, killing Garces along with 105 Spanish soldiers and settlers, taking at least 75 women and children captive. Spanish soldiers returned and battled the Indians over the next two years, killing more than a fifth of the Quechans, but then they were left alone until Americans arrived in 1846 during the Mexican War. A rush of Forty-niners to the California gold placers brought many Americans to Yuma crossing where the Quechan operated a ferry across the river until the business was usurped by Anglos. Hostilities increased when Quechan warriors felt the need to punish whites for stealing crops. But in 1857, the Quechan suffered a major defeat in a battle against the Pima and Maricopa tribes, leaving them demoralized with little enthusiasm for further warfare.

The Quechan obtained about half their food supply by planting fields in the low areas along the river, taking advantage of annual floods that deposited rich silt. Despite their brief contact with the Spanish, they obtained wheat and melon seeds to add to their native corn, beans and squash, especially pumpkin squash. The other half of the food supply came from fishing, hunting small game and gathering wild foods, most importantly, mesquite beans.

They lived in large extended families with patriarchal clan kinship. Like all Yuman speakers they cremated their dead along with all the deceased’s possessions. Spiritual belief required that important actions be dream-directed, with individuals who could best channel power through dreams taking leadership positions. Brutal warfare with neighboring tribes was a source of power, to control trade and territory, take captives and build social and spiritual esteem. The Quechan often allied with the Mohave against the Cocopahs and Maricopas.

While the Quechan helped travelers cross the Colorado far to the south, Mohave families ran a ferry for travelers along the Beale road. This woodcut was copied from a similar drawing that appeared in Lieut. Whipple’s railroad survey published in 1856. A man in the foreground is swimming sheep across while beyond the rafters a line of Whipple’s supplies is loaded onto an army boat. The Mohave built efficient rafts for crossing the river.

The Mojave Tribe (Tzi-na-ma-a, Pipa Aha Macav, Aha-Macave, Mohave)

Fort Mojave Indian Tribe and Fort Mohave Indian Reservation

A presidential proclamation March 30, 1870 created the Fort Mojave Military Reserve and the Fort Mojave hay and wood reserve, the latter meant to supply the fort. (See: Annual report of the commissioner of Indian affairs. . .1892) Apparently, Mojave families being held at the fort would be assigned work gathering wood and cutting hay. The military reservations would become de facto Indian reservations. The fort was given to the office of Indian Affairs by the military in 1890. But it would be another executive order February 2, 1911 that would convert the former military land into the Fort Mojave Indian Reservation. The reservation spans three states, 23,669 acres in Mohave County, Arizona; 12,633 acres adjacent to Needles, California; and 5,582 acres in Clark County, Nevada. Beginning at Laughlin, Nevada and Bullhead City, Arizona, reservation boundaries proceed south along the Colorado River, fragmenting into a checkerboard pattern of alternate sections of land ending at Topock Marsh. The other sections were originally part of the Atlantic & Pacific railroad land grant. The tribe spells Mojave with a “J” while the government now spells the name of the county and the reservation with an “H.” But the nineteenth century and 1911 documents used the “J” spelling.

Colorado River Indian Tribes and Colorado River Indian Reservation

The Colorado River Reserve, encompassing 376 square miles, was established by act of Congress March 3, 1865, for all tribes living along the river, the “Chemehuevi, Walapai, Kowia [Kawaiisu], Cocopah, Mojave, and Yuma tribes.” President Grant added more land to the Reserve November 22, 1873, November 16, 1874 and May 15, 1876. The expanded reservation began at the ruins of old La Paz, four miles north of Ehrenberg and ran north to Poston, then on both sides of the river to Monument Peak, in California north of Parker. Only a few Chemehuevi and Mojave were living in the area at that time. Placing the Mojave on separate reservations over three states would cause serious divisions within the tribe that persist to this day. The Colorado River Indian Tribes ratified a constitution July 17, 1937 and instituted a judicial system in 1940.

Suddenly, the War Relocation Authority decided to build Poston Relocation Camp in the middle of the reservation for Japanese-Americans who were American citizens but held as prisoners during World War Two. From 1942 until 1945 more than 30,000 Japanese Americans were held in Arizona at two concentration camps hastily built on Indian reservations. A third, virtually secret camp for “troublemakers,” was located at Leupp on the Navajo reservation. After the Japanese were released, renewed pressure came to bear upon Mojave and Chemehuevi residents of the reservation to give land to other Indians the government wished to relocate. Hopi families began arriving September 1, 1945 and Navajo families began coming in 1947, along with a few members of other tribes. Legal action by the Mohave and Chemehuevi ultimately halted immigration. But today, four tribes, Chemehuevi, Hopi, Mojave and Navajo, have a combined government on the reservation as the Colorado River Indian Tribes. They have senior water rights to nearly one-third of Arizona’s share of the Colorado River.

Because the Spanish had little sustained contact with the Mojave, history is vague until the American period. Despite the ferry service, relations with Americans deteriorated. Jedediah Smith reported being attacked by Mojaves in 1827 and an immigrant party on the Beale Road was attacked in 1858. The military established Fort Mojave the following year, three miles downstream from Hardyville crossing, but it had to be abandoned and burned when troops left to join the Civil War. The Fort was reestablished in 1863 then abandoned again in 1890. Like Ft. Yuma, the abandoned Ft. Mojave buildings were used by an Indian boarding school until 1930. But, unlike Ft. Yuma, only ruins remain today.

Like all Yuman speakers “The People by the River” (Pipa Aha Macav) trace their mythical origin to Spirit Mountain in Lake Mead National Recreation Area. Mojaves painted their bodies and tattooed their chins, but wore little clothing. Like the Quechan, the Mojave adopted warfare as a social institution for complex reasons tied to their magico-religious beliefs. Motivation probably included the martial spirit, which marked European cultures too. Allied with the Quechan, the Mojave suffered a significant defeat in a battle near Maricopa Wells against the Pima and Maricopa in 1857. They sometimes fought against and at other times had close relations with neighboring Pai tribes. Some Yavapai were reported to be living at the Ft. Mohave reservation. And a small number of Mojave ended up at the San Carlos Reservation for a time. The Fort McDowell Yavapai reservation is home to a sizable population of Mojaves. Over the years, the Mojave have been fractured as a tribe.

The Sovereign Cocopah Nation (Xawil Kunyavaei, Kwapa, Kwikapa)

Cocopah Indian Reservation

Apparently, the plan in 1873 was to relocate the Cocopah to the newly created Colorado River Indian Reservation, since the tribe is mentioned by President Grant as one of those for which the reservation was created. However, the Cocopah remained on their homelands south of Yuma until irrigation projects made the area attractive for agricultural development. A small reservation consisting of two noncontiguous parcels 13 miles south of Yuma was established 27 September 1917 by Executive Order. These enclaves, known as the west and east reservations, totaled 1,772 acres. April 18, 1985, Congress added a third enclave on the north and increased all three parcels to a total of more than 6,500 acres. The tribe adopted a constitution and formed a tribal council in 1964. The Cocopah Nation obtained senior water rights from the 1963 Supreme Court Case that apportioned Colorado River water between Arizona and California. At least 2,400 acres are now under irrigation and leased to non-tribal farmers. There are more than 1,000 tribal members.

Spanish adventurers found the Cocopah living along the Colorado River south of the Gila and all the way down to the delta at the Gulf of California. But the Gadsden Purchase (1853) ran an international border right through the tribe so that by 1930 the Cocopah in Arizona had been cut off from their kin, the Cucapá in Mexico. Cocopah families resisted formal assimilation but learned to work in Anglo communities, notably as riverboat pilots in the 1800s. Judged one of the ten poorest tribes in the US in 1970, the Cocopah Nation benefited from the American Indian Self-Governance movement, adding income from a casino and several recreational enterprises to the agricultural economic base. As a result, like nearly every other Arizona tribe, the Cocopah gained improvements in housing, education and community services.

The Cocopah traditionally led a dream-directed life like other river Yumans, but their most prominent ritual involved a six-day mourning rite for the dead, who were cremated along with their possessions. One of the tribal facilities today is a Cry House for funeral and remembrance ceremonies.

A number of Yuman speaking tribes were disrupted and relocated following contact with the Spanish and continuing warfare with the Quechan-Mojave alliance. In Arizona, these included the Hualapai, Akwa’ala, Halchidoma, Halykwanis, Kaveltcadoms, Kohuana, and Maricopas. The only Yuman speakers remaining on the Colorado River in Arizona were the Mojave, Quechan and Cocopahs. Among the Pimas, only some of the Maricopa and Halchidhoma now recognize their ancestry. (More on the Pimas and Maricopas in Part Four)

The Halchidhoma/Xalchidom

Originally inhabiting the lower Colorado River below the Gila, the Halchidhoma moved up river in the 18th century along with the Kohuana and then up the Gila in the 1820s to avoid warfare with the Quechan alliance. Most merged with the Maricopa tribe, but some settled on the Salt River where the town of Lehi (now north Mesa) would later be located.

The Halykwanis (Halyikawamai, Quicama)

Traditional enemies of the Quechan, this tribe was found by the Spanish (1540-1771) living on the east bank of the Colorado, north of the Cocopahs. But by 1775 Father Garcés noted they had moved to the west bank next to the Kohuana. Sometime after the Spanish left, the Halykwanis disappeared, probably absorbed by another Yuman speaking tribe. The Halykwanis and Kohuana spoke a dialect close to the Cocopah.

The Kaveltcadoms (Kavelchadom)

Once living along the lower Colorado River, north of its delta, the Kaveltcadoms had joined the Maricopas by 1840. They spoke a river branch dialect of the Yuman language family, similar to the dialects spoken by the Mohave, Quechan, Maricopa and Halchidoma.

The Kohuana (aka Coana, Kahwan, Cutganas)

This Yuman speaking tribe was living on the east side of the Colorado River below the Gila when encountered by Garces. Warfare with the Yumas and Cocopahs kept this tribe on the move, into California and at one time close to the present site of Parker. Defeated by the Yumas in 1781, they moved up the Gila River to merge with the Maricopas. In 1851, John R. Bartlett’s Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo boundary survey reported ten living with the Maricopas.

The Maricopa (Pipaash, Pee Posh, Pipatsje, aka Coco-Maricopas)

Evidence suggests that the Maricopas separated from the Quechan to avoid further warfare and moved up the Gila River to join with the Pimas. During or after this migration, the Maricopas apparently absorbed a number of other Yuman speakers, the Halchidomas, Kavelchadoms and Kohuanas.

The Southern Paiute Nation (Nuwuvi, Numu, Nüwü, Pah-Utes)

Southern Paiutes, a branch off Paiutes living in California, Nevada and Utah, formed small bands spread out over a large area, gaining a primitive living in a harsh environment. A dozen or more Paiute clans bound families to the dominating Ute Nation. The Southern Paiute grew corn, beans and pumpkins near streams or by damming and irrigating but depended on flat bread made from grass seed as their staple. They also hunted, from deer and wild sheep down to lizards and chipmunks. Important nourishment came from a large number of wild plants, including cactus and agave. They even knew how to obtain sugar crystals from willows and reeds.

Southern Paiute families went about on foot, clothing themselves with rabbit furs and grasses. They fashioned fine baskets, but few pots, carrying water in woven jugs caulked with pine pitch and cooking on rocks. They believed that the life force is present not only in humans, animals and plants but also every geographic and geologic feature of the landscape, even the air. Deceased ancestors become a part of the earth and their burial ground is a sacred place. Pilgrimages to special places had great importance.

American Indians speaking the Numic language of the Uto-Aztecan family were living in what is now northern Arizona and southern Utah when Spanish explorers ventured that far north in 1776. The Dominguez and Escalante expedition forcibly detained some of the “Payuchis” women near the present location of Cedar City, Utah, frightening all the Indians and leading the conquistadors to judge them “very cowardly.” Spanish and Mexican settlers, with the help of Ute Indians, were soon kidnapping Southern Paiute women and children for lives of servitude. The tribe’s next frightening encounter came with Americans following the Spanish Trail after 1826, who found the natives “wretchedly impoverished, living like animals.”

Anglos settled on Paiute lands grazing cattle and horses that ate all the grains that provided Indians with bread. Whites freely hunted wild game, while punishing starving Paiutes, sometimes with death, for hunting cows and taking horses. Relations with Americans deteriorated quickly and the Paiutes obtained guns from Mormon settlers after they were attacked by a non-Mormon wagon train in 1854. But the Southern Paiute bands had no tradition of warfare. And measles, smallpox and venereal disease greatly reduced their numbers, weakening their ability to oppose the loss of their land. The Black Hawk War in Utah introduced a period of Paiute and Navajo raiding and warfare with Mormon settlers 1865-1870. In the 1890s, the Ghost Dance religious movement, started by a Paiute in Nevada, spread to Arizona but failed to slow Anglo hegemony as promised.

The Spanish and Americans encountered several bands of Southern Paiutes living in Arizona, the Kaibab, San Juan, Uinkarets and Shivwits living north of the Grand Canyon and the Chemehuevi living along the Colorado River after it runs out of the canyon. Several other bands, among the 16 to 19 bands of Southern Paiutes, lived mostly in areas of Nevada and Utah but ranged into Arizona. The Kaiparowits, Paroosits and Moapats are three bands that used to venture into Arizona. There may have also been a distinction among the Indians themselves between eastern and western bands, what they called the Yanawants and the Paranayi. State borders divided up many of the Southern Paiutes leading to population disruption. And then there are the natural borders. The massive chasm of the Grand Canyon completely cut off two areas of Arizona. One is called the Arizona Strip, all of northern Arizona north and west of the Colorado River, historically more a part of Utah than the Grand Canyon State. The other is the Virgin River valley around Littlefield, Arizona in the extreme northwest corner of the state, an area that still has no access from Arizona except by leaving the state.

The Chemehuevi (Nüwü, Tantáwats)

Colorado River Indian Tribes and Colorado River Indian Reservation

Chemehuevi Indian Reservation (California)

In Arizona, about 800 Chemehuevi now live with three other tribes on the Colorado River Reservation (described above for the Mohave). Beginning in 1853, European settlers began displacing Chemehuevi families, but they managed to collect in the Chemehuevi Valley in California by 1885 where the Chemehuevi Valley Indian Reservation was created by the Department of Interior February 2, 1907. However, neither Congress nor the President acted to give the reservation force of law. Still, reservation land was allotted to individual Chemehuevis. A 1911 census found 246 members of the tribe living from Blythe to Needles to Twenty Nine Palms. By 1935 plans were underway to flood much of the Chemehuevi Valley under Lake Havasu behind Parker Dam. The federal government persuaded many families to relocate to the Colorado River Reservation 30 miles south and their status as a federally recognized tribe was lost in 1940. A 1951 lawsuit eventually provided $900,000 compensation for land submerged under Lake Havasu. Maintaining “a persistent desire for recognition and self-determination” over the next thirty years, the Nuwu people regained their federal tribal status in 1970.

The Chemehuevi, the southern most sub-tribe of the Paiute people, migrated south and east to live along the Colorado River, taking over territory vacated by the Hualapai and Maricopa. There, they came in contact with the Mohave, sometimes fighting them and at other times allied with them against other tribes. Under Mohave influence their dialect and habits strayed from their Paiute cousins. There also may have been extended contact with the Halchidhoma. The Chemehuevi traveled widely. Their traditional economy depended on foraging over a wide area of the Mohave Desert, leading them to adopt a routine of “being out.” Like the other Paiute bands, Chemehuevi baskets became widely renown for their craftsmanship.

Photographer J. K. Hillers, who accompanied Powell on his run through the Grand Canyon and subsequent trips to the Arizona Strip, posed Kaibab Paiute men in stereotypical ways that he believed would appeal to buyers of stereoscopic cards. This is a detail from an 1873 card titled “Making Fire.” Paiutes killed three men from the Powell expedition of 1869 who left the river and tried to walk out of the Grand Canyon. John Wesley Powell came looking for his missing crewmen in 1870 with the Mormon Apostle to the Lamanites (Indians) Jacob Hamblin and found the Paiutes friendly. Powell returned to the Arizona Strip 1871-1873 for mapping and again visited the indigenous people.

Kaibab Paiute youth examine “The Necklace” in this 1873 stereo view by J. K. Hillers. Powell and Hillers obtained buckskin clothing, probably from northern Paiutes, and dressed up the Kaibab Paiutes, apparently to make them look more grand and cover them up to avoid offending Victorian tastes. As a result, only their homes and habits were authentically pictured in the series. But the photos are virtually the only ones taken during this era. They sold well and made a nice profit for Powell. The two males wear unauthentic feather headgear like that worn by Paiutes in Nevada, while the four girls are identified by their bare knees.

The Kaibab Paiute Tribe (Kaivavwits)

Kaibab Indian Reservation

Settlers from Utah established ranches at Short Creek, Pipe Spring, Moccasin and Kanab Creek in 1863, in the heart of the hunting, gathering, growing and religious lands of the Kaibab band of Southern Paiutes. Anglos expropriated water sources and set loose cattle to graze the “open range.” After the reservation was created, non-Indians retained their farms, communities and water rights. One-third of the water from Moccasin Spring was allocated for the Paiutes in 1888.

The Moccasin Springs reservation was created by the Department of Interior 16 October 1907 for the Kaibab Paiute band, at which time families were issued cattle for their support. Additional cattle were given in 1916. The Kaibab Indian Reservation was established as a 12-mile by 18-mile rectangle by executive order 11 June 1913. President Wilson then issued another executive order 17 July 1917, removing from the reservation about 12 square miles surrounding the town of Fredonia. There is still an enclave of private land owned by non-Indians within the 120,413-acre reservation, 400 acres around the town of Moccasin. Moreover, in 1923, President Warren Harding designated 40 acres of reservation 12 miles west of Fredonia as Pipe Spring National Monument. This overlaid National Park Service administration on top of Bureau of Indian Affairs jurisdiction, to include an important water source. The Kaibab Paiute tribe has since reached agreement with the Park Service for water and business enterprise at Pipe Spring.

It wasn’t until 1951, that the Kaibab band adopted a constitution and tribal government, approved by the Secretary of Interior May 29, 1965. In 1956 the tribe argued before The Indian Claims Commission for restitution for the taking of aboriginal lands. A more than $1 million settlement was received in 1970 and a tribal administration building was dedicated in June of that year.

Kaiparowits Southern Paiute Band

Southern Paiute bands lived within territorial boundaries, ranging over a wide area to gather foods and find suitable land for small fields of crops. They migrated from plateau to valley with the weather. One band lived on the Kaiparowits and Aquarius Plateaus, on the north side of the Colorado River canyon (now Lake Powell) between the Henry Mountains and the Paria River. Lack of access to land and water for sustenance and exposure to European diseases caused the dissolution and relocation of the Kaiparowits band. A handful of Kaiparowits Paiutes were reportedly living near Escalante, Utah in the 1920s. A single individual still identifying with the band, named Tommy (or Timmican, after the famous Paiute chief), later moved to Richfield. (see: Loch Wade, “Do We Really Need Wilderness?” The Canyon Country Zephyr, April-May 2008.)

Moapa Paiutes (Moapats, Paranayi, Paranagat)

In the 1820s the Moapa band were growing corn, pumpkins and gourds along the Muddy River (in Arizona 1863-1866, now in Nevada). Mormons settled on the river in 1865, but had to abandon the area in 1871. The US Department of Interior established the Muddy Indian Reservation March 12, 1873, the first Paiute reservation in Nevada. The 3,000 acres were reduced to 1,000 acres in 1875. Mormon families who fled to Mexico to escape prosecution for polygamy returned to Muddy Valley in 1916 after the Mexican revolution.

Paroosit Band of Southern Paiutes (St. George band, Parrusits, Yanawant)

The Paroosits lived along the upper Virgin River (Par-roos river) from Pahvant Valley in Utah down to the Colorado River in Arizona and westward into Nevada at the mouth of the Virgin. With the Old Spanish Trail in their midst they suffered greatly from Mexican and American contact, finally scattering near Cedar City, Utah to find food. The last Paroosit reportedly died an old man in 1945 on the Santa Clara reservation.

San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe (Kwaiantikwokets)

This isolated southern Paiute band living east of the Colorado River ended up largely overlooked by the federal government because of its small population (62 individuals in 1873), and because it had affiliated with the Navajo. The tribe achieved federal recognition in 1990. It retains the largest proportion of speakers of the Paiute language of any Paiute tribe, about 10 percent. After living on the Navajo reservation for generations, the band (pop. now 300) signed a treaty with the Navajo Nation government May 20, 2000 to acquire rights to 5,100 acres of homeland near Hidden Springs, ten miles north of Tuba City, and 300 acres at Paiute Farms, south of Lake Powell near Navajo Mountain. Much of the Paiute Farms land had been lost under the waters of Lake Powell in the 1960s. The growth of tribal government led to factional disputes by 2007 and an FBI investigation of allegations of misuse of funds.

Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, Shivwits Band

Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah reservation, formerly the Santa Clara Indian Reservation

April 3, 1980, the federal government recognized the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, a composite of five Paiute bands terminated as recognized tribes by the federal government in 1954, the Cedar, Indian Peak, Kanosh, Koosharem and Shivwits bands. Some of these people had been building dams and irrigating fields along the Santa Clara River when a group of American trappers ran them off and burned all their homes and fields in 1826. The Americans’ motivation seemed to be disgust with the Indians’ “miserable” and “wretched” lifestyle.

The Shivwits band lived on the Shivwits Plateau, an extremely remote area of the Arizona Strip, across the Colorado River to the north from the Hualapai reservation. The southern fingers of the plateau are now a rarely visited part of Lake Mead National Recreation Area. Despite their isolation, Shivwits families suffered loss of their food supply upon the introduction of cattle ranching to the Strip by Mormons based in southern Utah. Heavy rains in 1882 and 1883 were followed by drought and periodic flooding through 1890. Drought killed half the cattle on the Arizona Strip that year. Concerned for their welfare and to stop them from eating his cattle, a prominent rancher made arrangements with the federal government to relocate the entire band of 194 individuals to the Santa Clara River in Utah where other bands of southern Paiutes had thinned out under economic pressures.

March 3, 1891, Congress authorized funding to acquire land and relocate the Shivwits band, the first action by the government on behalf of southern Paiutes anywhere in the US. The Secretary of Interior established the Santa Clara reservation November 1, 1903. Shebit Day School had opened in 1898 but closed in 1903. It relocated to Panguish as a boarding school the following year. An executive order of President Wilson 21 April 1916 defined reservation boundaries and increased total acreage to 26,800. Congress again enlarged the reservation in 1937. A tribal government was organized and a charter ratified August 30, 1941. Then federal policy turned to termination. Without fully explaining the consequences, the BIA convinced several Paiute bands to allow allotment of reservation land. September 1, 1954, Congress terminated the Shivwits, Kanosh, Koosharem and Indian Peak bands of Southern Paiutes living in Utah. Their water rights were transferred to Walker Bank & Trust Co. in Salt Lake City. Long after it had become clear that termination further impoverished Indian families, the four bands were restored to federal trust status in 1980 as the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah with their former reservation lands returned. A water rights settlement act passed in 2000 makes available 2,000 acre-feet annually from the water reclamation facility at St. George, Utah.

Uninkaret Band of Southern Paiutes

The Uninkarets lived on the Arizona strip around Mt. Trumbull. The Uinkaret Plateau lies between the Kaibab Plateau on the east and the Shivwits Plateau on the west. Three bands of Southern Paiutes identified with foraging lands on the three plateaus. But this harsh geography provided meager support. Though their fate is not clear, the Unikarets were reportedly “dispersed” in the late 19th century. A 1933 population count found 75 Kaibab Paiutes on the reservation at Moccasin, 50 Shivwits on the Santa Clara reservation and 50 Kumoits living around Cedar City. The Unikarets and several other bands were reported extinct.

See:

Stephen Dow Beckham, The Status of Certain Lands Within or Adjacent to the Chemehuevi Valley Indian Reservation, California, (1980s?)

Robert C. Euler, The Paiute People, (1972)

John I. Griffin, Today With the Havasupai Indians, (1972)

William Logan Hebner, Southern Paiute: A Portrait, (2010)

Frederick W. Hodge, Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, (1907)

Stephen Hirst, I Am the Grand Canyon: The Story of the Havasupai People, (2006)

Ronald L. Holt, Beneath these red cliffs: an ethnohistory of the Utah Paiutes, (2006)

Karl Jacoby, Crimes Against Nature. . ., (2001) [Havasupai]

A.L. Kroeber & G.B. Kroeber, A Mohave War Reminiscence 1854-1880, (1973)

Barry M. Pritzker, A Native American Encyclopedia, (2000)

Pat Stein, School Days at Truxton Canyon, (2002)

Stoffle, er al., Piapaxa ‘Uipi (Big River Canyon) . . ., (1994)

Stoffle, et al., Yanawant Paiute Places and Landscapes in the Arizona Strip, two volumes, (2005)

Angus M. Woodbury, A History of Southern Utah and Its National Parks, (1950)

Natale Zappia, “The One Who Wheezes”: Salvador Palma, the Colorado River, and the Emerging World Economy, (ca. 2003)

Sonoran Desert field trip guides

6 years ago