Roosevelt Survived the Flood

The town of Roosevelt is a service point for recreation on Roosevelt Lake, but it started before there was a lake, to provide goods and services to the workers building Roosevelt Dam. Back then it was located on the riverbank below the planned reservoir level. And as water rose behind the dam, the town had to move to higher ground to survive the flood. In fact, the lake rose behind the dam so rapidly during the spring of 1908 that many of the buildings were submerged before they could be moved, only to reappear during low water levels in the 1930s.

When construction workers first came in 1903, the project was called Tonto Dam or Tonto Basin Dam, after the valley that holds the lake. The dam would be built where the river was squeezed to 200 feet as it entered a rugged canyon just below a point called “The Crossing.” Exactly when the town came to be named Roosevelt is not clear. There is evidence that it was first called Newtown. But the Post Office was established January 22, 1904 as “Roosevelt,” and probably by then everyone knew it would be called Theodore Roosevelt Dam, after the president who supported its construction.

Looking west across a lazy Salt River about 1905, the dam site is in the canyon at right, with the town of Roosevelt spread across the only flat ground above the river. In another three years it would be inundated by the reservoir. Above the lake level, on Government Hill at left, are Reclamation Service buildings and tents for unmarried engineers. The largest building in front is the dining hall. The power canal is winding around the hills toward the damsite. On the hill at center is the cement plant. On the hill across the river is dam contractor O’Rourke’s camp. (I have added color to black & white photos for this post)

Looking NE over the town of Roosevelt in 1905, toward the frosted Sierra Ancha range, the main street business district is visible at the right edge. (click on picture for full size) Most of the houses are canvas tents with wooden walls and floors. In the lower left foreground is the electric plant, with a glimpse of the Salt River behind. East of town a road crossed the Salt and went 30 miles into the Sierra Anchas where the government built a sawmill to supply the project with at least three million board feet of lumber.

After 20 years of agricultural development beginning in 1867, many fortunes had been made in the Salt River Valley. But just as the ancient indigenous people who eventually abandoned their canals had learned, life in the irrigated oasis was always threatened by flood or drought. The spring freshet of 1886 washed out Arizona Dam at the head of the Arizona canal. Then the great flood of 1891 that put knee-deep water in the streets of Phoenix washed out all the dams on the Salt River. And as soon as the water drained away a period of severe drought set in until the end of the century.

Far-sighted individuals had already concluded there was need of a storage reservoir in the canyons of the Salt River, and the ideal site had been located in 1889, just below the confluence of the Salt with Tonto Creek. Despite agricultural bounty in the Valley, however, funding for such an ambitious project fell short. Private efforts failed twice. Meanwhile, flooding returned in 1900, only to be followed in 1901 by an all-time low level of water in the Salt River. Mass meetings were held in Phoenix’s Dorris Opera House and appeals were made to friends in Washington D.C. After Congress rejected the sale of Maricopa County bonds it provided a solution to the funding problem in the form of the National Reclamation Act, signed by Republican President Teddy Roosevelt June 17, 1902. It came at a time when the federal government was expanding its involvement in the states and the United States had become an imperial power to rival the empires of Europe.

Using the pooled resources of taxpayers across the country, the US Reclamation Service would provide millions of dollars to build the tallest dam in the country and the largest reservoir in the world, to block floods yet keep Salt River Valley canals full. It would be called the “Salt River Project,” the first of many reclamation projects in Arizona and among the first five in the country. Eleven private canal companies in the Valley were united in February 1903 to form the Salt River Valley Water Users Association, a non-profit irrigation company. Farmers and ranchers pledged to pay back the federal government loan, putting up their land as collateral. Hydropower generated by water releases at the dam would subsidize water delivery, with enough excess power to pump ground water beyond the end of canals. None of this came without opposition, but the majority prevailed.

This map prepared in 1910 by the Reclamation Service shows the site about 1907, but with a completed dam as it would appear in 1910. The main street of Roosevelt is at upper right, with the USRS office on Government Hill just below. Dam contractor O’Rourke’s camp is across the river by way of a suspension footbridge that washed away in 1908. The steam power plant, cement mill, sand crushing and concrete mixing plants are located. The power canal brought water to a temporary hydroelectric turbine located inside the penstock tunnel, putting the more costly steam plant on standby.

Roosevelt Dam was located in a very remote canyon 40 miles from the railroad at Globe and about 60 miles from Phoenix, inflating the cost of freighting supplies and adding to the difficulty of construction. Contractors reached the site from Globe in 1903, while construction of a road from Mesa, to be called the Apache Trail, continued for another three years. Houses for workers and a few stores were built on a hillside within walking distance of the dam site. The town and O’Rourke’s camp were provided with water and sewer lines, an ice plant, telephones and electricity. Roosevelt had utilities other towns in Arizona wished for. It also went without something every other boomtown had. The government forbade the sale of alcohol. Brick and lime kilns were completed in 1904, the same year a telephone line was strung to Phoenix and the road from Globe was completed. Work had begun on a cement plant. John M. O’Rourke & Co. of Galveston, Texas won the low bid to construct just the dam in March 1905 for a cost reported in the press of $1.1 million.

Though small and primitive motor trucks were available after 1905, large teams of draft horses or mules were still the best way to transport heavy loads beyond the railroad until well into the 1920s. All supplies for the work camp and construction were hauled over the shorter and relatively easier grades from Globe or the long and steep road from Mesa. The last two miles of the Mesa road were not completed until 1905. Freight made up 30% of the cost of supplies. Here, an empty oil tanker has stopped on the Apache Trail at J. Fraser’s Road House, a lodge at the bottom of Fish Creek Hill, before starting the difficult climb on the way to Mesa. (The postcard was published by the Berryhill Company of Phoenix and printed in Germany about 1907. Within a year or two American printers would install German presses and offer color postcards at a competitive price.)

So cement would not have to be freighted from Globe or Mesa, the Reclamation Service built (Nov. 1903-Mar.1905) a cement mill overlooking the damsite. Using limestone quarried right at the mill and clay from a mile away, the plant produced 338,452 barrels of cement from April 1905 to July 1910, for a savings of about $600,000. The mill used electricity and fuel oil, a barrel of oil for each four barrels of cement produced. The cost saving allowed the government to also ship barrels of cement from Roosevelt to the construction site of Granite Reef Dam in the Valley. A fire in the cement mill on December 7, 1908 caused a lot of damage and stopped work on the dam for two weeks.

To provide electricity, first a small wood-fired plant was built. It required 25 cords of wood a day and all scrub trees were soon stripped from the hills for ten miles around. An oil-fueled electric plant started up when oil delivery became available by mule wagons over the road from Mesa. Ultimately the plan was to use hydropower, and work began on a 19-mile power canal with 21 tunnels and two inverted siphons from a diversion dam on the Salt River. But it soon became apparent that the project would cost much more than first estimated. The power canal originally allotted $188,360 for construction gobbled up $1.4 million, plus another $127,000 for the diversion dam.

A 480-foot diversion tunnel, that could be used later to sluice silt from the lake, was bored through the south wall of the canyon in 1904. Cofferdams were built to isolate the worksite and the riverbed was excavated to bedrock over the winter of 1905-1906. In November 1905 came a flood of Biblical proportions. The river rose nearly 30 feet in 15 hours and overtopped the cofferdams. It became apparent that the diversion tunnel was too small and nothing could be done to prevent water from inundating the work every time the Salt River rose to flood stage. After years of drought, construction had unfortunately begun at the start of a period of record stream flows. Finally, the first stone was placed on clean bedrock September 20, 1906. Two months later work halted as the foundation stones disappeared beneath the raging river. Laying stones resumed in June 1907, interrupted by floods in summer and fall. While two years had originally been allotted for construction, four years, seven months and 21 days would pass before stones reached 150 feet on only the south side. It would require six years to complete 280 feet of masonry running 723 feet between spillways.

Here, on July 16, 1906, workers are rebuilding the downstream cofferdam, using a “hydraulic lift” much like a canal lock, to lift excavated material. Digging reached bedrock 30 feet below the river surface where foundation stones were laid in cement mortar on the thoroughly washed bedrock. In December, the Salt River flooded, overtopping the cofferdams and washing away everything seen here. But the cemented stones didn’t budge.

A close-up of construction late in 1907 shows how the dam was engineered. The masonry technique was termed “broken range cyclopean rubble,” placing large irregular blocks of sandstone weighing up to 10-tons each with the joints breaking rather than aligned. Each block was completely surrounded with at least two inches of concrete, with spalls (splinters of rock) added to fill wide gaps. Workers are adding another block at lower right with a tub of concrete at ready, as an engineer in white shirt and tie observes. Pipes deliver water to drench the stones and keep the concrete from drying before it sets. Blocks at the vertical upstream face were finished with a chisel to produce a uniform wall with random projections. Blocks were finished where they made the sloping downstream face to present an aesthetic stair-step surface. (This picture is a detail from a postcard made by German printers who colorized a black & white photograph sent to them by publisher M. Rieder of Los Angeles. Each card coming from a two-color press had additional colors laboriously added by hand with a brush and bottles of dye.)

After two years of frustrating work between floods the project was way behind schedule. Here, on April 29, 1908, sandstone blocks are about 50 feet above bedrock on the south side. But the river is running over the north side while the sluicing tunnel is closed off (bottom left) to install gates from January 31 to July 2. Behind the masonry rubble the hydropower house can be seen. High on the canyon wall at right stones are quarried, then moved by overhead cable and derricks to their place on the dam. The quarry will become the north spillway. An overhead cableway (two black squares are pulleys) delivered stones each night, tubs of concrete mortar all day. The concrete mixing facility is on the side of the canyon at left. The High Line road to Mesa (later called Apache Trail) is precariously cut into the cliffs above the river.

A view of the dam from downstream in late summer 1908 shows the south side rising above 70 feet and work restarted on the lower north side after the sluicing tunnel reopened. The powerhouse is enclosed and water can be seen exiting the tunnel below the building. December 16, 1908, water again overtopped the dam, a stream 125 feet wide and 13 feet deep, not receding until the end of the month. Again, the deluge came so suddenly workers could not save derricks and winches from being swept away.

The sluicing tunnel was closed off again May 8, 1909 so concrete and steel lining could be added to repair cavitation damage. Shutting off irrigation in the valley during the growing season was unacceptable, so workers had to cut a notch in the dam to pass enough water for the crops. Masonry has passed the 130-foot level on the south side and an electric substation building has been added in the foreground. The cableway at upper right is delivering a tub of concrete. The boardinghouse at O’Rourke’s camp can be seen on the hill behind the dam.

By November 1, 1909 the dam was almost 200 feet high on the south side. A week later the sluicing gates would reopen, diverting the river from flowing through the notch on the north side so work could resume there. Stonemasons were working on an ever-narrowing summit. The dam was 167 feet thick at bedrock but only 16 feet at top, enough weight of rock to easily hold back the weight of water 270 or more feet deep. In this photo you can clearly see the vertical upstream face with random projections and the stair-step downstream face. Workers living at O’Rourke’s camp reached the town of Roosevelt by boat after a footbridge suspended across the canyon washed away. They went to work by crossing the notch on the smaller footbridge at lower right.

Immigrants were welcomed as cheap labor in the United States in those days and many different nationalities, including native-born Blacks, worked at Roosevelt. Italians were adept stonecutters. Apache men did much of the work on the road that would later be named after them, proving particularly skillful at laying dry masonry to support the roadbed on the side of cliffs. Still, a strict segregation of labor was maintained, with Anglos in supervisory positions and people of color assigned manual labor.

The temporary hydropower plant provided electricity from April 1906 until August 1909. At that time the permanent hydropower plant constructed (1906-1908) of stone on the south side of the river started up three turbines. In October 1909 electricity was supplied to Valley cities over a 75-mile, 45,000-volt transmission line constructed 1907-1909. Water was supplied to Valley canals at Granite Reef diversion dam (constructed by the Reclamation Service Oct.1906-Aug.1908).

Cost of the dam had ballooned past $3 million, far above the original estimate of $1.9 million. Add to that the expensive power canal, at least a million dollars spent acquiring land and another $2.3 million for the electric power system. “Because of heavy flooding that wreaked havoc with the construction site, it may have been impossible for any company or organization to have built Roosevelt Dam in a timely, cost effective manner,” concluded an official history (Billington, et al., 2005). Flooding showed the need, but residents in the Salt River Valley became impatient for completion and unhappy with Reclamation Service performance and looked for ways to reduce the cost they would have to repay. The last stone on the dam was finally laid February 5, 1911, but O’Rourke’s workers had already begun leaving during the previous year.

After signing the Reclamation Act, President Theodore Roosevelt was reelected in 1904. He declined to run again in 1908 but remained a popular and influential public figure. Here, he arrives from Phoenix by car March 18, 1911 with Territorial Governor Richard Sloan to dedicate the government dam named in his honor.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, army guards were assigned to prevent sabotage of important infrastructure, including the nation’s largest hydroelectric dam in the remote mountains of the newest state. This detail from a Keystone View Company stereoscopic card shows a contingent of “Sammies” near the south end valve house.

Another two generators were added at Roosevelt Dam in 1912, and spillways were raised five feet in 1913. A sixth generator was added in November 1915. After five years only half full, rain in the mountains filled the lake to 225 feet at the dam and water first began to flow through the spillways on the evening of April 15, 1915. Repairs to the spillways were made from October 1915 to January 1916, and completed just four days before the next spillover. Roosevelt Lake reached a maximum storage of 1.5 million acre-feet, and 2.1 million acre feet were measured over the spillways from January 18 through May 30, 1916. The water level almost touched the underside of the automobile bridges on each side and the dam shook for weeks as if by an earthquake under the weight of water eleven and a half feet deep rushing through the spillways.

Though mailed in 1921, this postcard probably shows the 1915 spill when water first overflowed the dam. The former O’Rourke camp, now Roosevelt Lodge, is at Hotel Point. After overflowing in 1915 and 1916, Roosevelt Lake overflowed again in 1920 before entering a long period of drought. Following the installation of three penstock valves before 1920 in the north canyon wall, water could be released through the south wall sluicing tunnel, hydropower turbines, the spillways, two north wall tunnels and the penstock valves. But the appearance of the dam had been designed to suggest strength under all that weight of water.

Upon completion of the dam, buildings at O’Rourke’s camp were sold to local merchants M. C. Webb and his son. The boarding house became Roosevelt Lodge to accommodate tourists as the sights along the Apache Trail were publicized far and wide. Visitors could ride a bus over the Trail and eat or stay at Tortilla Flat, Fish Creek Lodge or Roosevelt Lodge. Apache Indian families were put on display and Anglo traders sold Native American crafts. In addition to the dam, tourists could visit nearby Tonto National Monument ruins or take a boat out on the lake.

In 1917, the Southern Pacific railroad purchased the hotel and renamed it Apache Lodge. While the Union Pacific railroad bused tourists to the north rim of the Grand Canyon and Santa Fe railroad trains went directly to the south rim, the Southern Pacific promoted Apache Trail and Roosevelt Lake. Railroads also connected with bus and car transportation to a number of Arizona dude ranches and hot springs.

The final cost of the project came to more than $10 million and the ten-year repayment schedule had to be extended to twenty by an act of Congress in 1914. In 1917, the Reclamation Service turned over operation of Roosevelt Dam to the Water Users Association, retaining mortgage holder interests. But the Association could not make loan payments during the recession years of 1920 and 1921. As soon as the economy improved, the Association sold bonds to build five additional dams on the Salt and Verde Rivers beginning in 1923. That same year, spillway gates were added to Roosevelt Dam, raising the lake another 15 feet, and in 1936 spillway floors were improved to minimize damage during overflow. By 1925 irrigation and power infrastructure represented an investment of more than $23 million. In 1937, the Association created the Salt River Project Agricultural Improvement and Power District, an autonomous government entity, so the state legislature could grant it favorable municipal bonding powers. Drought nearly emptied Roosevelt Lake by June 1940. Then it quickly filled and spilled over in 1941. After World War Two, the Association had trouble paying taxes, so it transferred the electric utility to the tax-exempt District, creating today’s SRP. In 1955, water users paid off the federal loan thirty-five years late.

Thaddeus T. Frazier opened a store at Roosevelt in 1908. It hosted the Post Office for many years, with Stella Frazier as postmaster 1916-1958. (The postcard was published around 1952 for the Fraziers by Norton Louis Avery & Son of Lowell, Michigan and printed in “Genuine Natural Color” by Dexter Press of West Nyack, New York.)

Carson’s Café, cabins and boats was located on the west side of Cottonwood Creek or wash, where the marina is now. This postcard shows the resort about 1962, with Rock Island behind the trees and the highway cut going around to Government Hill visible at upper left. In 1988, work began to reroute Highway 88 and relocate recreational facilities in anticipation of higher reservoir levels after the dam was raised. As a result, only traces of older facilities can be seen today. But again, Roosevelt survived the flood.

The need for more water, earthquake protection and a calculated increase in the volume of “hundred-year floods” caused the federal government in 1984 to authorize raising the height of Roosevelt Dam. Work started in 1989 but had to be delayed when the Salt River again produced a torrent. Storms in the watershed brought the lake to its highest level ever on January 19, 1993. The south spillway could not channel all the flow and water overtopped the sidewall and began pouring onto the roof of the hydropower house, causing a million dollars damage. By then a new 1,080-foot long suspension arch highway bridge had opened behind the dam. When work resumed on the dam, the front was covered over with concrete to thicken it and raise it. At a cost of $424 million the top of the dam was raised 77 feet. Now, only at low water levels can the original sandstone blocks be seen on the upstream wall. Since the original structure had disappeared, the dam’s National Historic Landmark status designated in 1963 was withdrawn in 1999.

See:

Donald N. Bentz, “The Doomed City” Frontier Times May 1968.

David P. Billington, et al., The History of Large Federal Dams. . . (US Bureau of Reclamation, 2005)

Kathleen Garcia, Roosevelt Dam (2009)

Athia L. Hardt, ed., Arizona Waterline [1989]

L. L. Lombardi, Tortilla Flat Then & Now (1996)

Salt River Project, The Taming of the Salt (1970)

Stephen C. Shadegg, Century One (1969)

Chester W. Smith, “The Building of the Roosevelt Dam” The Earth August 1909

Karen L. Smith, The Magnificent Experiment, Building the Salt River Reclamation Project, 1890-1917 (1986)

US Dept. of Interior, USGS, US Reclamation Service, annual reports: 1903-04, 1915-16.

Earl A. Zarbin, Roosevelt Dam: A History to 1911 (1984)

Monday, December 27, 2010

Monday, November 29, 2010

Quartzsite Was In the

Center of Everywhere

The small town of Quartzsite is sprawled out about 5 miles along Interstate-10 in western La Paz County, 19 miles east of Ehrenberg. It extends another five miles north and south of the freeway along State Route 95, which follows Tyson Wash across the La Posa Plain north to the Colorado River. The open desert sizzling in summer heat, surrounded by jagged mountains, gives the impression of a way station in the middle of nowhere, but the estimated 1.5 million yearly visitors suggests Quartzsite is the center of everywhere. Residents have been able to make the location on a well-traveled route pay off in a big way while providing visitors with a memorable experience.

History tells us Charles Tyson built a non-military fort at the location in 1856 to protect the water supply from Mohave-Apache (Yavapai) raids. That was the year of the first rush to the gold placers in Yuma County, and very early in the area’s history, leaving little documentation now. Arizona Territory was not separated from New Mexico until 1863. A historical marker at the site gives 1864 as the probable date Tyson hand dug his well. The Quartzsite Historical Society believes Tyson built the still extant adobe stage station in 1866. That year, the California & Arizona Stage Company began running passengers, mail and Wells Fargo express from the end of the Southern Pacific track in California to Ehrenberg and Wickenburg. Ehrenberg, Arizona was a steamboat landing on the Colorado River, supplying the interior via freight wagons. The river towns of Ehrenberg, Olive City and La Paz served miners during the 1860s Colorado River gold rush. Gold had also been recently discovered around Wickenburg and in the mountains south of Prescott. The stage road forked at Wickenburg, with stages going north to the territorial capital at Prescott and south to Phoenix and Florence.

There are four or five types of desert in Arizona. Quartzsite is near the northern limit of the Sonoran Desert, with the Mohave Desert to the northwest. To the southwest, the landscape differs from the desert around Phoenix and Tucson. Traditionally, this sparse cover in Yuma County and southern California has been called the Colorado Desert, though some authorities say it’s still part of the Sonoran. The Chihuahuan Desert also extends into Arizona around Douglas and San Simon. And parts of northern Arizona along the Utah border resemble the Great Basin Desert. Burton Frasher of Pomona published this Real Photo Post Card, likely in the 1940s.

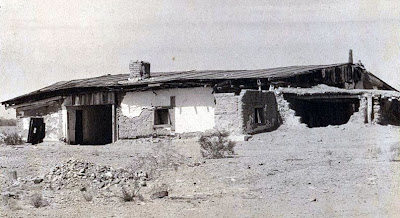

Frasher also preserved this view of Tyson’s Well stage station looking SE with the highway in the foreground. It may not have been called a fort until the 20th Century. Plaster on the walls and a metal roof has helped preserve the long-abandoned adobe structure.

This photo of Tyson’s, looking northwest at the back of the building, probably dates to the 1940s. Additions without the metal roof are crumbling. The tip of the saguaro cactus in Frasher’s photo is visible above the roof at right. Photographer Glenn Edgerton carefully documented much of the Mohave Desert of California and Arizona.

Tyson’s Well stage station continued to provide rest and refreshment to travelers and freight drivers until the railroads came in the 1880s. Martha Summerhayes, wife of an Army officer stationed in Arizona, described travel in those days. Transferred with her husband from Camp Verde to Ehrenberg, she found way stations along the road primitive but welcoming, with one exception. After three days, the Army wagons entered the Colorado Desert and stopped for the night at Desert Station in Bouse Wash. She again found accommodations “clean and attractive, which was more than could be said of the place where we stopped the next night, a place called Tyson’s Wells. We slept in our tent that night, for of all the places on the earth a poorly kept ranch in Arizona is the most melancholy and uninviting. It reeks of everything unclean, morally and physically.”

Tyson’s Well revived in the 1890s when more efficient gold mining methods were introduced to the area. Several families opened stores, taverns and hotels to serve nearby mines. A post office was established as “Tyson’s” in the summer of 1893 but discontinued in the fall of 1895. A year later the post office reopened under the name “Quartzsite.” Quartzite (without the “s”) is a rock of firmly cemented quartz grains. Lacking experience in prospecting, the postal service apparently registered the name as a place where quartz is found.

But the mining boom soon faded and there were less than 20 residents by 1900. Location again came to the rescue about ten years later when the Atlantic and Pacific automobile road was routed through Quartzsite. Cross-country travelers could avoid the Imperial Sand Dunes west of Yuma by heading from Phoenix to Wickenburg, Quartzsite and Ehrenberg. There, they crossed the Colorado River to Blythe on a small ferry boat and went on to Los Angeles. Every year after 1911 more and more cars made the trip.

Looking east about 1915 along the Atlantic & Pacific Highway through Quartzsite, the Hagely Hotel is on the left. German immigrant Anton Hagely (1844-1928) worked as a butcher in town during the 1890s mining boom and stayed on to become owner of a store and hotel. Upon his death, his wife Victoria continued the business. Their son John George (1894-1977) became a Quartzsite Justice of the Peace. Down the street on the same side, with windmill and water tank out front, is Charles V. Kuehn’s general store. Kuehn (1886-1930) was a former stage driver who came to own a store and saloon. He was also postmaster 1914-1923.

Looking west along Highways 60/70, part of nearby Granite Mountain is visible at left behind the store. The Hagely Hotel is the building in center, not with the Shell sign. It has a sign that says “Motel.” Quartzsite had declined a bit when this photo was taken about 1933 by Burton Frasher. By then automobiles made fewer stops on long trips. Maybe just gas and soda pop at Quartzsite before speeding on to Ehrenberg where a through-truss bridge had replaced the ferry in 1928. By then the Atlantic & Pacific Highway had been numbered state route 74. In the 1930s the highway became part of US60 and US70.

In 1856 the US Cavalry imported 33 camels as an experiment to see if they should replace horses and mules in the southwest deserts. But the animals ended up at the relatively high altitude of Fort Verde and were used during construction of the Beale Wagon Road across the plateaus of northern Arizona. The camel corps was disbanded in 1864. One of the camel drivers, a Greek-Syrian going by the name Hadji Ali, a.k.a. Phillip Tedro (1829-1902) but informally known by the more pronounceable “Hi Jolly,” settled in Quartzsite as a prospector. In 1935, in order to publicize US 60, the Arizona Highway Department built this pyramid tombstone to honor the Muslim who was “over thirty years a faithful aid to the U.S. government.” Hi Jolly’s grave is still a popular visit in Quartzsite. Hollywood cowboy actor Buck Conner (1880-1947) is also buried there. Conner was the brother of Mrs. W. G. Keiser (1877-1939) who with her husband operated Beacon Hotel and store for about 15 years in Quartzsite. Highway Color postcard by Bolty, published by Frye & Smith Ltd. of San Diego.

This view of the old adobe stage station about 1965 shows some restoration work, though half of the building has collapsed into ruin since the older photos were taken. The Quartzsite Historical Society completed additional restoration work and opened Tyson’s Well Museum in the building in 1980. Photo by Bob Van Luchene published by Petley Studios of Phoenix.

Quartzsite’s population of a few hundred in the 1930s had declined to just 50 by 1960. In 1965 residents formed the Quartzsite Improvement Association which sponsored the first Pow Wow Gem & Mineral Show in 1967 drawing 74 exhibitors and vendors and about 1,000 visitors. This postcard shows the event a few years later when it drew crowds estimated at more than 12,000. The view is to the southwest with the freeway crossing Tyson’s Wash at upper right, just after passing under Highway 95. South of the freeway are some of the RV camps. The Quartzsite experience blossomed and now offers winter visitors a number of gem and mineral shows in addition to a gigantic flea market. The town incorporated in 1989 and includes a public library, bank, medical centers, golf course and more than 70 RV and mobile home parks. In 2006 more than 2,000 people there were working for the government, with another 2,775 employed in the services industry. The “dry camping capital of the world” and “rock hound paradise” hosts an estimated 250,000 temporary residents each winter.

See:

Arizona Good Roads Assoc., Tour Book (1913)

“Genealogy of the People of Quartzsite” website http://utahrockhounds.com/quartzsitegen/

Richard J. Hinton, Handbook to Arizona (1877)

Hirum C. Hodge, Arizona As It Is. . .1874-1876. (1877)

Palo Verde Historical Museum & Society, Blythe & the Palo Verde Valley (2005)

Martha Summerhayes, Vanished Arizona (1908) quote is from pp. 145-6 of 1911 edition.

Roanna H. Winsor, “Monument to Hi Jolly,” Arizona Highways May 1961.

Center of Everywhere

The small town of Quartzsite is sprawled out about 5 miles along Interstate-10 in western La Paz County, 19 miles east of Ehrenberg. It extends another five miles north and south of the freeway along State Route 95, which follows Tyson Wash across the La Posa Plain north to the Colorado River. The open desert sizzling in summer heat, surrounded by jagged mountains, gives the impression of a way station in the middle of nowhere, but the estimated 1.5 million yearly visitors suggests Quartzsite is the center of everywhere. Residents have been able to make the location on a well-traveled route pay off in a big way while providing visitors with a memorable experience.

History tells us Charles Tyson built a non-military fort at the location in 1856 to protect the water supply from Mohave-Apache (Yavapai) raids. That was the year of the first rush to the gold placers in Yuma County, and very early in the area’s history, leaving little documentation now. Arizona Territory was not separated from New Mexico until 1863. A historical marker at the site gives 1864 as the probable date Tyson hand dug his well. The Quartzsite Historical Society believes Tyson built the still extant adobe stage station in 1866. That year, the California & Arizona Stage Company began running passengers, mail and Wells Fargo express from the end of the Southern Pacific track in California to Ehrenberg and Wickenburg. Ehrenberg, Arizona was a steamboat landing on the Colorado River, supplying the interior via freight wagons. The river towns of Ehrenberg, Olive City and La Paz served miners during the 1860s Colorado River gold rush. Gold had also been recently discovered around Wickenburg and in the mountains south of Prescott. The stage road forked at Wickenburg, with stages going north to the territorial capital at Prescott and south to Phoenix and Florence.

There are four or five types of desert in Arizona. Quartzsite is near the northern limit of the Sonoran Desert, with the Mohave Desert to the northwest. To the southwest, the landscape differs from the desert around Phoenix and Tucson. Traditionally, this sparse cover in Yuma County and southern California has been called the Colorado Desert, though some authorities say it’s still part of the Sonoran. The Chihuahuan Desert also extends into Arizona around Douglas and San Simon. And parts of northern Arizona along the Utah border resemble the Great Basin Desert. Burton Frasher of Pomona published this Real Photo Post Card, likely in the 1940s.

Frasher also preserved this view of Tyson’s Well stage station looking SE with the highway in the foreground. It may not have been called a fort until the 20th Century. Plaster on the walls and a metal roof has helped preserve the long-abandoned adobe structure.

This photo of Tyson’s, looking northwest at the back of the building, probably dates to the 1940s. Additions without the metal roof are crumbling. The tip of the saguaro cactus in Frasher’s photo is visible above the roof at right. Photographer Glenn Edgerton carefully documented much of the Mohave Desert of California and Arizona.

Tyson’s Well stage station continued to provide rest and refreshment to travelers and freight drivers until the railroads came in the 1880s. Martha Summerhayes, wife of an Army officer stationed in Arizona, described travel in those days. Transferred with her husband from Camp Verde to Ehrenberg, she found way stations along the road primitive but welcoming, with one exception. After three days, the Army wagons entered the Colorado Desert and stopped for the night at Desert Station in Bouse Wash. She again found accommodations “clean and attractive, which was more than could be said of the place where we stopped the next night, a place called Tyson’s Wells. We slept in our tent that night, for of all the places on the earth a poorly kept ranch in Arizona is the most melancholy and uninviting. It reeks of everything unclean, morally and physically.”

Tyson’s Well revived in the 1890s when more efficient gold mining methods were introduced to the area. Several families opened stores, taverns and hotels to serve nearby mines. A post office was established as “Tyson’s” in the summer of 1893 but discontinued in the fall of 1895. A year later the post office reopened under the name “Quartzsite.” Quartzite (without the “s”) is a rock of firmly cemented quartz grains. Lacking experience in prospecting, the postal service apparently registered the name as a place where quartz is found.

But the mining boom soon faded and there were less than 20 residents by 1900. Location again came to the rescue about ten years later when the Atlantic and Pacific automobile road was routed through Quartzsite. Cross-country travelers could avoid the Imperial Sand Dunes west of Yuma by heading from Phoenix to Wickenburg, Quartzsite and Ehrenberg. There, they crossed the Colorado River to Blythe on a small ferry boat and went on to Los Angeles. Every year after 1911 more and more cars made the trip.

Looking east about 1915 along the Atlantic & Pacific Highway through Quartzsite, the Hagely Hotel is on the left. German immigrant Anton Hagely (1844-1928) worked as a butcher in town during the 1890s mining boom and stayed on to become owner of a store and hotel. Upon his death, his wife Victoria continued the business. Their son John George (1894-1977) became a Quartzsite Justice of the Peace. Down the street on the same side, with windmill and water tank out front, is Charles V. Kuehn’s general store. Kuehn (1886-1930) was a former stage driver who came to own a store and saloon. He was also postmaster 1914-1923.

Looking west along Highways 60/70, part of nearby Granite Mountain is visible at left behind the store. The Hagely Hotel is the building in center, not with the Shell sign. It has a sign that says “Motel.” Quartzsite had declined a bit when this photo was taken about 1933 by Burton Frasher. By then automobiles made fewer stops on long trips. Maybe just gas and soda pop at Quartzsite before speeding on to Ehrenberg where a through-truss bridge had replaced the ferry in 1928. By then the Atlantic & Pacific Highway had been numbered state route 74. In the 1930s the highway became part of US60 and US70.

In 1856 the US Cavalry imported 33 camels as an experiment to see if they should replace horses and mules in the southwest deserts. But the animals ended up at the relatively high altitude of Fort Verde and were used during construction of the Beale Wagon Road across the plateaus of northern Arizona. The camel corps was disbanded in 1864. One of the camel drivers, a Greek-Syrian going by the name Hadji Ali, a.k.a. Phillip Tedro (1829-1902) but informally known by the more pronounceable “Hi Jolly,” settled in Quartzsite as a prospector. In 1935, in order to publicize US 60, the Arizona Highway Department built this pyramid tombstone to honor the Muslim who was “over thirty years a faithful aid to the U.S. government.” Hi Jolly’s grave is still a popular visit in Quartzsite. Hollywood cowboy actor Buck Conner (1880-1947) is also buried there. Conner was the brother of Mrs. W. G. Keiser (1877-1939) who with her husband operated Beacon Hotel and store for about 15 years in Quartzsite. Highway Color postcard by Bolty, published by Frye & Smith Ltd. of San Diego.

This view of the old adobe stage station about 1965 shows some restoration work, though half of the building has collapsed into ruin since the older photos were taken. The Quartzsite Historical Society completed additional restoration work and opened Tyson’s Well Museum in the building in 1980. Photo by Bob Van Luchene published by Petley Studios of Phoenix.

Quartzsite’s population of a few hundred in the 1930s had declined to just 50 by 1960. In 1965 residents formed the Quartzsite Improvement Association which sponsored the first Pow Wow Gem & Mineral Show in 1967 drawing 74 exhibitors and vendors and about 1,000 visitors. This postcard shows the event a few years later when it drew crowds estimated at more than 12,000. The view is to the southwest with the freeway crossing Tyson’s Wash at upper right, just after passing under Highway 95. South of the freeway are some of the RV camps. The Quartzsite experience blossomed and now offers winter visitors a number of gem and mineral shows in addition to a gigantic flea market. The town incorporated in 1989 and includes a public library, bank, medical centers, golf course and more than 70 RV and mobile home parks. In 2006 more than 2,000 people there were working for the government, with another 2,775 employed in the services industry. The “dry camping capital of the world” and “rock hound paradise” hosts an estimated 250,000 temporary residents each winter.

See:

Arizona Good Roads Assoc., Tour Book (1913)

“Genealogy of the People of Quartzsite” website http://utahrockhounds.com/quartzsitegen/

Richard J. Hinton, Handbook to Arizona (1877)

Hirum C. Hodge, Arizona As It Is. . .1874-1876. (1877)

Palo Verde Historical Museum & Society, Blythe & the Palo Verde Valley (2005)

Martha Summerhayes, Vanished Arizona (1908) quote is from pp. 145-6 of 1911 edition.

Roanna H. Winsor, “Monument to Hi Jolly,” Arizona Highways May 1961.

Sunday, November 7, 2010

Phoenix Was Both

Part Two: The Struggle To Maintain Paradise

Oasis and Mirage

Part Two: The Struggle To Maintain Paradise

(Part One is below, posted 22 Oct 2010)

When the economy crashed at the end of 1929, Phoenix was facing a long hard slog to try to maintain a lifestyle that had only been attained by higher income families. Though Phoenix fared better than most eastern localities, by 1933 almost 10,000 people in the city of about 50,000 were receiving some kind of welfare benefits (p.103, Luckingham, Phoenix, 1989). And there was little money to improve social conditions or infrastructure. Even after war industries brought wealth into the valley, poverty remained a problem. In 1950 the Los Angeles Examiner found a family of seven starving in a labor camp near Phoenix. The father was “a cripple” and sold his blood for food, which ran out before he could sell more. African-American residents in Phoenix were often denied welfare benefits during the Great Depression and had to form their own charitable organizations. Franciscan Father Emmett McLoughlin came to Phoenix in 1933 and spent his life working to improve the south side. He founded a hospital and advocated slum clearance and construction of low-cost public housing. By the 1960s, Phoenix was still unable to provide a decent living for all its residents.

Phoenix could measure up to any American city when it came to bootlegging, drug abuse, illegal gambling, prostitution and public corruption. “Every conceivable kind of illegal activity seemed to flourish in the rapidly emerging metropolis, including white-collar and organized crime” (p.209, Luckingham, Phoenix, 1989). Just before World War Two, the military came to the valley for its good flying weather and built five Army air bases: Luke Field, Williams Field, Falcon Field, and Thunderbird No. 1 and 2. The Navy, in partnership with Goodyear tire opened an aircraft factory and air station. Phoenix and other valley cities were suddenly flooded with jobs and government contracts. But the Army, in order to protect its soldiers, demanded Phoenix clean up vice, and especially, end prostitution. As a result, city leaders at least made their community appear more respectable. But the war did bring lasting change. Factories without smoke stacks, predominately aerospace and electronics plants, began replacing the agricultural economic base.

Looking west along the Grand Canal toward St. Francis Xavier Parish church (1928), probably in the 1930s, illustrates the pastoral landscape created upon application of large amounts of water to the fertile desert soil. When the supply of water ran short forty years later, shady but thirsty cottonwood trees were cut down and the canal lined with concrete. St. Francis, located on Central Avenue south of Camelback Road and a few blocks north of Phoenix Indian School, was also home to Brophy College Preparatory School, still the valley’s leading Catholic high school.

Development of railroads offered the possibility of growing a lucrative tourist industry in the valley. Phoenix got a Southern Pacific railroad mainline in 1926 to replace the branch line from Maricopa, bringing winter visitors without a change of trains. Winter resorts like Ingleside Inn (1910) and Arizona Biltmore (1929), shown here in 1936, catered to an upscale clientele. The Biltmore, located about 8 miles NE of Phoenix, was built by the McArthur Brothers who owned a Dodge dealership on Central & Madison. Albert McArthur, who once worked for Frank Lloyd Wright, designed the building in Prairie School style, constructed of decorative cast concrete blocks. The economic downturn forced the brothers to sell to chewing gum magnate William Wrigley, Jr. who built a huge mansion nearby. (See: “A Biltmore Myth,” by Avis Berman, Western Interiors Jan-Feb 2005, pp.57-65)

By 1937, despite the Depression, middle-class families were taking to newly paved highways on cheap vacations. By 1935, Phoenix was located on two cross-country highways, numbered 70 and 80, and two more federal highways crossing the state, north-south Highway 89 and west-east Highway 60. This 1937 ad in Better Homes and Gardens offered a blooming oasis and recommended permanently relocating to Phoenix. The “Valley of the Sun” moniker was adopted in 1934 (p.110, Luckingham, Phoenix, 1989).

Despite the worst economic conditions ever seen, a number of new industries first developed in the 1920s continued to grow in the 1930s, including the highway system, scheduled airline service, bus transportation, motor hotels, radio, cinema with sound and color, self-service supermarkets, iceless refrigeration, and air conditioning. Various air cooling methods began to appear in the 1920s in larger hotels. Some theaters were cooled by blowing air over tons of ice in the basement. Evaporative coolers became common on Phoenix homes in the 1930s. Refrigerated air conditioning, called “dry” air conditioning at the time, was installed in all the Luhrs office buildings in 1932. The Luhrs Hotel became the first refrigerated-AC hotel in Phoenix in 1936. Air conditioning made life in Phoenix enjoyable year-round. “Picture yourself actually leading the sort of leisurely, tranquil, do-as-you-please existence you’ve always wanted, and you’ll have some faint idea of what life is like in this happy, carefree Valley of the Sun Vacationland,” enticed a 1942 Phoenix tourism promotion.

Following World War II, Americans took to the highways in greater numbers and Phoenix was transformed. The main highway from the east, Van Buren Street became lined with a seemingly endless supply of neon marked auto courts, color flagged gasoline stations and cafes surrounded by cars. US 80 left Phoenix on two lanes of concrete with expansion joints along West Van Buren in those days, while US 60 went up Grand Avenue toward Glendale. Today, the site of the Park Lane is a parking lot for the Arizona Dept. of Revenue building.

South Pacific ambience was popular after Hawaii became a state in 1959 and the hospitality industry in Phoenix continued for many years to play upon Hawaiian or Polynesian themes. Examples include Samoan Village, Coconut Grove Motel, Trader Vic’s restaurant in Scottsdale and the Kon Tiki Hotel at 2463 E. Van Buren, shown here about 1962. “A little bit of Waikiki in the heart of Phoenix” opened in 1962 and was popular for decades. Freeways, nationwide chains and franchises eventually depressed the Van Buren hospitality corridor and Kon Tiki was torn down in the 1990s to make way for a parking lot. (See: “Lei’d To Rest. . .” by Dewey Webb, New Times, 15 Dec. 1993; “No Vacancy at Log Cabin Motel,” by Robert L. Pela, New Times, 18 Mar. 2010)

This photo of PHX Sky Harbor about 1965, looking SE shows the $850,000 Terminal One (1952) with circular parking lot and $2.7 million Terminal Two (1962) to the east. Across the runway is the Arizona Air National Guard, Boeing C-97 tanker base. In the middle of landlocked Arizona, a harbor for aircraft officially opened September 2, 1929. The City of Phoenix purchased the facility in 1935. In 1946, largely due to good flying weather, Sky Harbor was the busiest airport in the nation. And there were no accidents of any kind that year. By 1947, TWA was operating 21 flights a day into Phoenix. Terminal One was demolished in 1990, though the tower was saved and relocated.

This photo from about 1957 of the intersection of Washington and Second Streets looking west shows the original City Hall Plaza now occupied by J. C. Penney’s (1953) and Fox Theatre (1931). Within ten years, the big chain stores would begin moving away from the downtown and Washington Street would empty. Today, the block on the left is a parking lot, just as it was during the Depression, 1928-1953. Suburban shopping led to deterioration of the downtown, followed by several attempts to revitalize the urban core.

Phoenix was always a low-density city. But, as the spacious lifestyle attracted more residents, subdivision and strip-mall development spread out for miles. Air pollution, heat islands, bumper-to-bumper traffic and long commutes would eventually threaten the leisurely lifestyle. Phoenix sold its buses to a private company in 1959, only to buy back the failing system in 1971. George Luhrs, Jr., an early high-rise developer and director of the Chamber of Commerce, said in later years that he “preferred gradual growth and was not anxious to see it become a large wicked city, sprawling over a large part of the county, destroying much of the desert, eliminating much of the agriculture and the citrus land.” The population of Phoenix increased 311% during the 1950s, boosted by aggressive annexation.

Black Canyon, the first freeway in Phoenix opened in November 1960 but extended for only seven miles. In this photo, looking south, by Herb McLaughlin, probably from 1963, the McDowell Road overpass can be seen in the distance, before there was an I-10 stack. In the 1950s, Phoenix’s straight and wide streets seemed ideally suited to automobiles while traffic was still light. Freeways were built relatively late, too late some said at the time. In 1973, Phoenix voters said no to an inner loop freeway. Two years later government convinced voters to change their minds. Still, there were only 32 miles of freeway in 1980.

Another building boom downtown began about 1962 and this view looking NE about 1966 shows some of the early projects. At left is First Baptist Church (1929) with the red roof, on the NW corner of Third Avenue & Monroe. Panning right, on Adams Street are two buildings (1928 and one with tall windowless tower 1953) of Mountain States Telephone & Telegraph (now Quest & AT&T), then the tall, black First American Title (1964), 111 W. Monroe, with First National Bank (Phoenix Title & Trust Bldg., 1931) in front, then older buildings along Central Avenue. In the foreground are government buildings along Jefferson Street, the Municipal Complex (1963) with round council chambers, the old City-County Courthouse (1929) with orange roof, and two blocks between Jefferson and Madison filled with Maricopa County Complex (1965). The slim Luhrs Tower (1930) and the Luhrs parking garage are to the right. Hotel Westward Ho with TV tower is at upper center. Uptown Business District high-rise buildings around Central & Osborn can be seen at upper left.

The Salt River Valley really isn’t a valley. The many square miles of wide open and fairly flat land that offered early settlers the prospect of easy farming is actually a series of flood plains along stream beds and alluvial slopes coming down from the mountains. As development expanded floods threatened. Heavy rain flooded Phoenix homes twice in 1963. A deluge of rain came in June 1972, draining away down Indian Bend Wash. Large areas of Scottsdale submerged under five or more feet of water. Storm runoff broke the banks of the Arizona Canal flooding Phoenix neighborhoods all the way to the north Central Avenue business district. A 1993 flood in the Salt River virtually cut off transportation between Phoenix and Tempe. Despite the appearance of an abundance of water, flood irrigation, ornamental fountains spraying into the air, homes on the shores of artificial lakes, Phoenix has long suffered from a water shortage. As Phoenicians worked to build the lush oasis, sometimes their goals remained in the distance, staying just out of reach, like a shimmering mirage on the desert.

Despite all its problems, Phoenix still seemed to have fewer difficulties than other urban areas in the 1950s and 60s. For many middle class families during those years life was good. New homes, mid-century modern designed churches, schools and commercial buildings were going up everywhere. Cheap recreational opportunities abounded. In Papago Park you could climb Hole In the Rock, tour the botanical garden, play golf, go to the zoo, or go just across Van Buren Street to enjoy the rides at Legend City amusement park or watch Major League baseball practice in winter. During those decades, even lower income residents could believe life was improving and civilization progressing. Arizona Highways magazine observed in 1964, “when men like builder John Long appeared on the scene offering three-bedroom homes with swimming pool for $11,600, housing in Phoenix started to change. There is no other city in the United States that, dollar for dollar, can offer the value to be found in Phoenix. Low cost housing remains one of the strongest factors in the changing face of Phoenix.”

Despite all its problems, Phoenix still seemed to have fewer difficulties than other urban areas in the 1950s and 60s. For many middle class families during those years life was good. New homes, mid-century modern designed churches, schools and commercial buildings were going up everywhere. Cheap recreational opportunities abounded. In Papago Park you could climb Hole In the Rock, tour the botanical garden, play golf, go to the zoo, or go just across Van Buren Street to enjoy the rides at Legend City amusement park or watch Major League baseball practice in winter. During those decades, even lower income residents could believe life was improving and civilization progressing. Arizona Highways magazine observed in 1964, “when men like builder John Long appeared on the scene offering three-bedroom homes with swimming pool for $11,600, housing in Phoenix started to change. There is no other city in the United States that, dollar for dollar, can offer the value to be found in Phoenix. Low cost housing remains one of the strongest factors in the changing face of Phoenix.”

Park Central Shopping Center opened in 1957 at 3418 N. 7th Avenue, two miles north of the state capitol, and became the city’s first mall. It was later called Park Central Shopping City, then Park Central Mall and is now known simply as Park Central, with mixed use by offices and small shops. It began a change in the way city dwellers shopped, moving away from the previous practice of walking sidewalks among storefronts and instead, driving a personal automobile to a parking lot in front of a strip mall. Then in the 1960s, enclosed walking malls became the ideal. Now, shopping seems to be returning to strip malls—and something different, big box stores. Phoenix has seen it all, and can serve as an object lesson.

The 1960s building boom saw the first tall buildings on north Central Avenue close to Park Central Mall. This 1963 view of the intersection of Central & Osborn (lower left corner) shows (from left) Executive Towers apartments (completed 1964) at 22 stories (207 W. Clarendon, converted to condos in 1971), Guaranty Bank (1960) at 20 stories, and Del Webb Building (1962) at 17 stories (3800 N. Central, remodeled in 1989). In the foreground is Osborn School, soon to be demolished for the construction of Financial Center (1964, heightened in 1968). Part of Osborn School, half the two-story building in center, was built in 1892. Another high-rise, Del Webb Towne House at 23 stories was added in 1964 in the block north of the Del Webb Building.

This photo taken by Don Keller in September 1963 shows a small portion of the Arcadia neighborhood, looking west, with Arcadia High School barely visible at top (click on picture to see full size) and Indian School Road following the Arizona Canal at top right. Osborn Road is lined with trees, running in front of Ingleside Junior High and what will become Arcadia Park (at right). The “T” intersection at lower left is 56th Street (running left to right) and Earll with a nearly full parking lot at the Motorola plant. Arcadia, at the base of Camelback Mountain northeast of Phoenix and just west of Ingleside, was planted in citrus groves beginning in 1919. You can see remnants of citrus rows in the photo. It soon became an elite location for estates. When this photo was taken, it was an example of one of the finest neighborhoods for middle class families with good incomes, offering spacious lots and large ranch style homes with pools. The line of homes at bottom borders Arizona Country Club (1946). Motorola opened a research and development facility at 56th Street & Earll in 1950. It became an electronics factory 1962-1982. Today it’s an office. And an EPA Superfund Site since 1989, the origin of an underground water pollution plume of cadmium, chromium, arsenic and solvents that has migrated all the way to downtown Phoenix. There is a cleanup process now in place.

Construction continued downtown with more and taller buildings darkening streets. This view from about 1977 shows one of the last rows of old buildings along Washington opposite Patriots Square (1974). The intersection in the foreground is Jefferson and First Avenue. Facing the square (from left) is the former J. J. Newberry 3-story building (1937), a rebuild of the old Monihan Building, the 4-story former S. H. Kress store, the 2-story former site of J. C. Penney and the 6-story Goodrich Building. Looming over this block in the background are (from left) the high-rise Arizona Bank (1976, now US Bank), Valley Center (1972, now Chase), rebuilt Adams Hotel (1975, now Wyndham), and Hyatt Regency (1976) with revolving restaurant on top. There was another pause in downtown construction during poor economic conditions 1976-1986. Then the old buildings in this view were demolished for construction of Renaissance Square (1987 & 1990).

See:

Arizona Development Board, The Arizona Story, (ca1962)

Arizona Highways, August 1943, “Phoenix. . .a frontier town that grew up” (entire issue)

Arizona Highways, April 1957, “Phoenix—City In the Sun” (entire issue)

Arizona Highways, March 1964, “The Changing Face of Phoenix” (entire issue)

Holy Trinity Greek History Committee, Greeks In Phoenix (2008)

Arthur G. Horton, An Economic, Political & Social Survey of Phoenix. . . (1941)

George H. N. Luhrs, Jr. (1895-1984), The George H. N. Luhrs family in Phoenix. . . (1984) manuscript at ASU Library.

Emmett McLoughlin (1907-1970), People’s Padre, (1954)

Lowell Parker, Arizona Towns & Tales, (1975)

Phoenix & Phoenix Union High School, http://www.acmeron.com/index.html

Phoenix - rising out of the ashes, http://www.bradhallart.com/phoenix.htm

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Report on Flood of 22 June 1972. . . (1972)

Van Buren, as it used to be, http://www.sierraestrella.com/vanburen.html

Friday, October 22, 2010

Phoenix Was Both

Oasis and Mirage

Soon after Arizona Territory was created from the western half of New Mexico enterprising individuals were drawn to the fertile soil of the Salt River Valley and the remains of ancient canals built there by Native Americans. In 1865, John Y. T. Smith located a hay cutting camp to supply Fort McDowell where 40th Street now meets the airport. About two years later a group of investors from Wickenburg led by Jack Swilling had two of the old canals cleaned out to irrigate wheat fields and supply a flourmill located on high ground about a mile east of where the downtown is today. Both Swilling and a friend named Darrell Duppa likely named the collection of farms and worker houses around the mill “Phoenix Settlement,” predicting a great civilization would rise from the ruins of the ancients. In May 1868, Yavapai County created the Phoenix election precinct in the valley.

Wickenburg and the Colorado River towns of Aubry, La Paz and Castle Dome were experiencing a gold rush at the time and supplies for miners were in great demand. Fresh fruit and vegetables were very expensive or just not available. But with irrigation, the Salt River Valley could grow enough grains, fruit, vegetables and beef to supply the entire territory. A number of individuals recognized this and came to Phoenix Settlement with big dreams of creating a lush oasis in the desert, growing enough wealth to rival any mining town in the territory. The climate would permit more than one harvest in a year. With the Verde, Salt and Gila rivers all coming together nearby, there would be water in abundance. And the central location would make for economical transportation of goods to every corner of the territory. And wealth buys political power. With Prescott and Tucson vying to be Territorial Capital, Phoenix could offer a compromise location half way between the two.

In October 1870, those with money to invest got together and voted to establish a new city called Phoenix west of the Settlement. Streets were surveyed, those running east and west named after US presidents with north-south streets named after Indian tribes. It would be a rigid grid plan based on the axis formed by Washington and Centre Streets. The first street west of Centre was Cortez, conqueror of the Indians, while the first street east was Montezuma, the conquered. Two blocks were reserved for the public, a plaza at Washington and Montezuma with a courthouse square at Washington and Cortez. Oh yes, the following year Phoenix became county seat of the newly created Maricopa County, though the county court would have to rent a room in Phoenix for a few years. Swilling’s settlement, now known as Mill City or East Phoenix, just couldn’t compete. The new Phoenix went straight to the head of the line.

In 1885, when this lithographic birds-eye-view was published in San Francisco, Phoenix was still a small village though promising a big future. The Maricopa County Court House (1884), No. 1, occupies one public square, while the Plaza, No. 13, fills another. The two-story brick Central Grammar School, No. 4, is at upper left, with a public swimming pool, No. 15, near a source of water, the “town ditch,” No. 6, that used to run along Van Buren Street until it was channeled underground in 1927. The first church in town, Centre Street Methodist Church (1871), is marked No. 5 and there is another Methodist Church (No. 3) on Washington Street. The first store in town, Hancock’s (1871), No. 10, is located on the NW corner of Washington and Montezuma. The Irvine Block (1879), No. 14, second brick structure built, is on the SW corner of Washington and Montezuma. The first brick building faces the opposite corner of the Plaza, on the SE corner of Jefferson (next street south of Washington) and 2nd Street. Sacred Heart of St. Louis Catholic Church (1881), No. 19, is at 316 E. Monroe. J. Y. T. Smith’s steam-powered flourmill is No. 12 on Jefferson Street. Notice the telegraph line. Electric power for lights would be available the following year. Much of the north side of Washington Street’s business district burned in 1885 and then again in 1886.

In 1885, when this lithographic birds-eye-view was published in San Francisco, Phoenix was still a small village though promising a big future. The Maricopa County Court House (1884), No. 1, occupies one public square, while the Plaza, No. 13, fills another. The two-story brick Central Grammar School, No. 4, is at upper left, with a public swimming pool, No. 15, near a source of water, the “town ditch,” No. 6, that used to run along Van Buren Street until it was channeled underground in 1927. The first church in town, Centre Street Methodist Church (1871), is marked No. 5 and there is another Methodist Church (No. 3) on Washington Street. The first store in town, Hancock’s (1871), No. 10, is located on the NW corner of Washington and Montezuma. The Irvine Block (1879), No. 14, second brick structure built, is on the SW corner of Washington and Montezuma. The first brick building faces the opposite corner of the Plaza, on the SE corner of Jefferson (next street south of Washington) and 2nd Street. Sacred Heart of St. Louis Catholic Church (1881), No. 19, is at 316 E. Monroe. J. Y. T. Smith’s steam-powered flourmill is No. 12 on Jefferson Street. Notice the telegraph line. Electric power for lights would be available the following year. Much of the north side of Washington Street’s business district burned in 1885 and then again in 1886.

The 1885 lithograph was framed with pictures of important buildings, like this view of the first hotel in town, John J. Gardner’s Phoenix Hotel. Constructed in 1871-1872 of adobe surrounding an inner court with a swimming pool, it typified the early “Mexican style” buildings that were more comfortable in the heat and cheaper to build than wood construction. But brick buildings gave the impression of solid Anglo prosperity so a kiln opened in 1879.

The 1885 lithograph was framed with pictures of important buildings, like this view of the first hotel in town, John J. Gardner’s Phoenix Hotel. Constructed in 1871-1872 of adobe surrounding an inner court with a swimming pool, it typified the early “Mexican style” buildings that were more comfortable in the heat and cheaper to build than wood construction. But brick buildings gave the impression of solid Anglo prosperity so a kiln opened in 1879.

In 1873, a nationwide economic recession dried up investment money and slowed growth in Arizona. Still, the population of Phoenix rose from 240 in 1870 to 1,708 by 1880. Nine years later Phoenix became the capital of Arizona Territory. By then the town of about 3,000 was surrounded by thousands of acres of field crops, cow pasture and orchards. Canals and laterals brought water everywhere. A rail line connecting with Maricopa carried boxcars of grain, dried fruit and fresh vegetables to far away markets. Land development and tourism grew as fast as crops in the field. The Salt River Valley “offers rich inducements to the Capitalist, the Home-seeker and the Tourist” promised a promotional ad (Pacific Monthly November 1906). “The mild winter climate of this valley brings great relief to those who are tired of cold winds, snow and ice.” The dry air also cured lung diseases, giving rise to sanitariums amongst the citrus groves.

A steam powered tractor runs a threshing machine as out in the field a reaper continues to cut, in this postcard view published about 1909. At the time, there were about 125,000 acres under cultivation in the Valley. Roosevelt Dam was nearing completion with the promise of much more water for irrigation. By 1925, more than half of all land under cultivation in Arizona was located in the Salt River Valley. And Arizona ranked first in the nation for acres of domesticated hay (mostly alfalfa), and first for production of grain sorghums per acre.

A steam powered tractor runs a threshing machine as out in the field a reaper continues to cut, in this postcard view published about 1909. At the time, there were about 125,000 acres under cultivation in the Valley. Roosevelt Dam was nearing completion with the promise of much more water for irrigation. By 1925, more than half of all land under cultivation in Arizona was located in the Salt River Valley. And Arizona ranked first in the nation for acres of domesticated hay (mostly alfalfa), and first for production of grain sorghums per acre.

Construction of this City Hall was completed in 1888 in the middle of the Plaza on Washington between First and Second Streets. City government had been incorporated in 1881. The bell tower was a 1905 addition. Behind the building and to the right you can see the bell tower of the fire station on the SW corner of the Plaza. The City Hall building was a powerful inducement to bring the capital to Phoenix in 1889 since the legislature and the Governor were offered the upper floor until a capitol building could be completed. Economic hard times put off the start of capitol construction until 1899 and it was completed in 1901. City offices moved into one side of a new City-County building in 1929 and old City Hall was demolished. What had been a public square was sold for business development. Fox Theater was built on the NW corner of the block. Years later a new J. C. Penney store was built on the NE corner.

Construction of this City Hall was completed in 1888 in the middle of the Plaza on Washington between First and Second Streets. City government had been incorporated in 1881. The bell tower was a 1905 addition. Behind the building and to the right you can see the bell tower of the fire station on the SW corner of the Plaza. The City Hall building was a powerful inducement to bring the capital to Phoenix in 1889 since the legislature and the Governor were offered the upper floor until a capitol building could be completed. Economic hard times put off the start of capitol construction until 1899 and it was completed in 1901. City offices moved into one side of a new City-County building in 1929 and old City Hall was demolished. What had been a public square was sold for business development. Fox Theater was built on the NW corner of the block. Years later a new J. C. Penney store was built on the NE corner.

Phoenix had been a fairly controlled city from its inception. Appearance and reputation were important to satisfy investors, property buyers, government officials and visitors. Soon after it became territorial capital, residents looked toward statehood. The wild west image stood in the way. Phoenix formed a vigilance committee in the 1870s to deal harshly with lawlessness. By 1896, the New York Tribune noted that the city of 10,000 required “in the daytime only one policeman, and hardly requiring him.” Multi-story brick commercial buildings and landscaped homes with wide verandas presented a prosperous and peaceful appearance. “The old adobe of the early pioneer is fast disappearing before the march of progress,” reassured Meyer’s Business Directory in 1888. It concluded that “Phoenix has fairly entered upon the road which leads to prosperity,” quoting a report in the Albuquerque Democrat. “Sustained and supported by the vast tract of rich and productive soil which surrounds it on all sides, with abundance of water and a perfect climate, she can look to the future with serene confidence.”

The intersection of Washington and 1st Avenue is shown here about 1907. Without air conditioning of any kind, only electric fans, shopping and working heavily clothed in brick and wooden buildings, Phoenix residents spent most summer days very uncomfortably. Awnings over the sidewalk and on the upper floors of the Fleming Building, and the shades hanging from the front of the Monihan Building balcony were necessities. Parasols shield passengers in open carriages. A few automobiles appeared about this time, but horses were everywhere until after 1910. By 1914 there were 400 automobiles registered in Phoenix.

The intersection of Washington and 1st Avenue is shown here about 1907. Without air conditioning of any kind, only electric fans, shopping and working heavily clothed in brick and wooden buildings, Phoenix residents spent most summer days very uncomfortably. Awnings over the sidewalk and on the upper floors of the Fleming Building, and the shades hanging from the front of the Monihan Building balcony were necessities. Parasols shield passengers in open carriages. A few automobiles appeared about this time, but horses were everywhere until after 1910. By 1914 there were 400 automobiles registered in Phoenix.

The first Adams Hotel building (1896), of brick with wooden porches all around, is on the right, a block away, in this view from about 1907. On the left side of the street with blue roof and white spire is Center Street Methodist Church (1871). The Goodrich Building (1886) is at left (with awnings) when it was only one story tall. The business district ended at Van Buren, where the trees are, and a prime residential neighborhood extended a few blocks north.

The first Adams Hotel building (1896), of brick with wooden porches all around, is on the right, a block away, in this view from about 1907. On the left side of the street with blue roof and white spire is Center Street Methodist Church (1871). The Goodrich Building (1886) is at left (with awnings) when it was only one story tall. The business district ended at Van Buren, where the trees are, and a prime residential neighborhood extended a few blocks north.

The 1879 brick schoolhouse visible in the lithograph above, on the block bounded by Van Buren, Monroe, Center and 1st Avenue, was expanded in 1893, again in 1899, and is pictured here about 1908 or earlier. Before the brick building, the first classes were held in one room of an adobe building constructed in 1871 on First Avenue south of Washington and rented by the county court. In 1873 an adobe schoolhouse was built, visible in the lithograph just east of the brick building. An 1889 postcard shows two more school buildings by then, East End School and West End School. The central building was the High School. A high school district was organized in 1895 with high school students sharing Central School with elementary school students, but in 1897 the Churchill mansion on Fifth Street just north of Van Buren was donated. It became Phoenix Union High School. The school district did not maintain the Central School building well and it was demolished in 1920. In 1928 the San Carlos Hotel and the Security Building were built on the site.

The 1879 brick schoolhouse visible in the lithograph above, on the block bounded by Van Buren, Monroe, Center and 1st Avenue, was expanded in 1893, again in 1899, and is pictured here about 1908 or earlier. Before the brick building, the first classes were held in one room of an adobe building constructed in 1871 on First Avenue south of Washington and rented by the county court. In 1873 an adobe schoolhouse was built, visible in the lithograph just east of the brick building. An 1889 postcard shows two more school buildings by then, East End School and West End School. The central building was the High School. A high school district was organized in 1895 with high school students sharing Central School with elementary school students, but in 1897 the Churchill mansion on Fifth Street just north of Van Buren was donated. It became Phoenix Union High School. The school district did not maintain the Central School building well and it was demolished in 1920. In 1928 the San Carlos Hotel and the Security Building were built on the site.

This is Washington at First Street, looking west about 1911. The corner of the Irvine Block is at left, with the plaza farther left out of view. At right is the Anderson building, former home of B. Heyman Furniture Company, but now housing the Berryhill Company, stationers. Minus the two towers, the building survived into the 1980s. The site is now occupied by Phelps Dodge Tower. Streetcars made suburban living possible. In 1887, the first horse-drawn streetcars began bringing shoppers to Washington Street at a time when there were few sidewalks and streets were unpaved. Electricity replaced horses in 1893 but the streetcars were still small, four-wheeled conveyances. By the time this photo was taken, larger streetcars were in use. The main line north went up First Street (where one car is turning). Streetcars stopped running in 1948, replaced by buses. Now, after great effort and expense, they are back.

This is Washington at First Street, looking west about 1911. The corner of the Irvine Block is at left, with the plaza farther left out of view. At right is the Anderson building, former home of B. Heyman Furniture Company, but now housing the Berryhill Company, stationers. Minus the two towers, the building survived into the 1980s. The site is now occupied by Phelps Dodge Tower. Streetcars made suburban living possible. In 1887, the first horse-drawn streetcars began bringing shoppers to Washington Street at a time when there were few sidewalks and streets were unpaved. Electricity replaced horses in 1893 but the streetcars were still small, four-wheeled conveyances. By the time this photo was taken, larger streetcars were in use. The main line north went up First Street (where one car is turning). Streetcars stopped running in 1948, replaced by buses. Now, after great effort and expense, they are back.

By 1900 Indian street names had been replaced with numbers, Avenues on the west side of Center, Streets to the east. Centre Street became “Center” and finally Central Avenue. This view of Washington (with streetcar) and First Avenue (with mid-street parking) looks northeast from the courthouse cupola about 1918. The Fleming Building (built in 1893, raised to 4-storys in 1896, demolished 1970), with Phoenix National Bank, is at left with a flag. Across the street is the Monihan Building (1889) and at the east end of the block is the 4-story Goodrich Building (raised to 6-stories in 1921). The white building seen above the Monihan Building is the Adams Hotel (rebuilt 1911 after a fire) with “wireless” antennas (2-way radio) on the roof. Panning to the right, you can see St. Mary’s Catholic Church (1915) in the distance, and closer, on 1st Street, Dorris-Heyman furniture store (white, four-story) and part of top floor of Korrick’s (1914) department store (tan color). Postcard published by A. O. Boeres, Phoenix, through Curt Teich American Art company.